Spending an entire day in an air-conditioned room, and then walking to a car that has been basking all day, is an extreme sport that many of us face. But people have overlooked that these temperature changes are determined and regulated by design. Some time ago we reported the danger of leaving children in a hot parked car. However, there are more designed microclimates in cities, with somatosensory temperatures well above the reported temperatures. The nursery is an example of children spending a lot of time in a day, where we find that some artificial surfaces may become dangerous.

The author conducted a preliminary study in the summer of 2017-8 to evaluate the thermal characteristics of outdoor play spaces at three child care centres in Western Sydney. I have found that summer temperatures can vary significantly, depending on the material and environment being measured. We measured air and surface temperatures to generate detailed information about the effect of heat on the shaded and non-shaded surfaces of each facility. These include man-made materials such as “soft fall” surfaces and Astroturf; semi-natural materials such as bricks and wood chips; and natural materials including sand and grass.

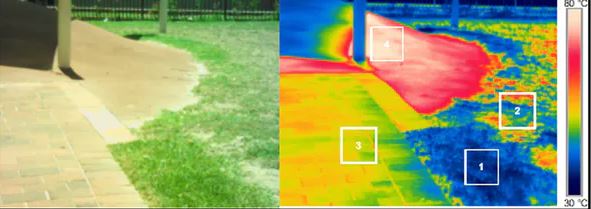

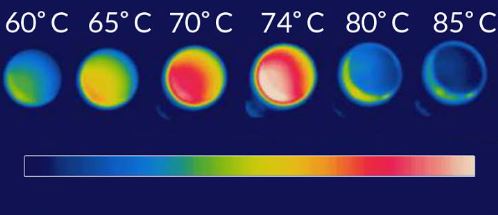

In full sunlight, artificial surface materials become very dangerous. In days where the temperature is below 30 seconds, the soft surface temperature in autumn reaches 71-84 ° C. Astroturf is heated to approximately 100 ° C. Plastic toys in direct sunlight can reach a temperature of 73.7 ° C-this is a hot rubber duck! See the effect of different surfaces in the thermal image below. It shows tens of degrees of difference between soft fall and thick grass in sunny conditions.

Thermal material destroys safety benefits

As the name suggests, softening materials are widely used to create a “safer” environment for children to fall. Rising heat undermines this safety. Because it turns the material into potentially significant harm, it also reduces outdoor play time. Contrary to their current widespread use, the study found that artificial materials such as soft pendants and Astroturf should be reduced and used only in cool places. Shadows do have a significant effect on recorded temperatures, but it’s not surprising that a center with an ancient camphor tree provides plenty of shadows in the game space, recording the lowest daytime temperatures. A hot and healthy outdoor play space is essential to support children’s social, physical and cognitive development. However, the extreme temperatures recorded in this study turned such spaces into hostile environments and had no choice but to move indoors to cope.

Indoor activities tend to be sedentary, which is related to decreased fitness and increased obesity. We have spent about 90% of our time indoors (including cars) in indoor environments (including cars) to suit the living environment. Of course, you can only effectively air-condition a space if it is enclosed. The rise of “indoor biomes” is related to poor air quality and a number of other complex hazards. However, a child care center with a cool, comfortable outdoor play area is designed to enable people to move and connect with nature, but it is far from standard in our rapidly growing city. For example, the latest center in our study has the smallest outdoor activity space, the least shadows, very limited natural floor coverage, and the greatest degree of soft fall. This raises questions about the impact of design trends on the quality of outdoor activity spaces. It is also worth noting that given the level of demand, there are often few options for providing accommodation for children.

Climate change makes design more important

Should designers be responsible for the everyday environment they create? For example, can past designers understand the environmental, social, and cultural impact of one of the most transformative cars of the 20th century? Maybe not, but things have changed. The need to adapt to a changing climate makes good design vital to our survival. This, in turn, requires designers to take greater responsibility for the injuries caused by their work. In the U.S., the latest report from the Environmental Law Foundation and the Boston Green Ribbon Commission puts the role of adaptation strategies in regulations, planning, and design as new urgency. The report found that voluntary measures did not make a significant difference in planning, design or development practices. These continue to operate according to past, not current or future climate patterns. In Australia, following the 2017 Great Fire of the Grenfell Tower in England and the 2014 Lacrosse Apartment Fire in Melbourne, Australia, the National Building Code was revised to require more stringent testing of exterior walls and cladding. But the code still doesn’t take into account “hail, storm surge, or specific requirements related to thermal stress.”

Resilience to current and expected environmental changes requires updated design standards. Designers need better training and support to foresee harm and creatively deal with conditions we may never have encountered before, even if their clients do not require it. After all, the lifespan of many design products, structures, and environments may far exceed the lifespan of humans. This means that design decisions made now will be left to future generations. Since the summer of 50 degrees Celsius before mid-century is expected to happen regularly, now we need to design cities differently. This places responsibility on all those involved in the planning, design and architecture professions. Traditionally, it was not a required part of their practice, but it should be. Although the measurement is uncertain due to the emissivity (the degree of thermal energy emitted by the material), the higher temperature of the building facade during the day indicates an influence on the observed temperature of the near facade. By considering design drivers-including direction and daylight, material albedo (reflectivity) and emissivity, and the landscape of the building and sky opposite-the architects can cool our city with “cool exterior walls.”

Buildings are key to outdoor comfort

Previous research has linked surface roughness to reflectivity characteristics. The potentially contradictory effects of sidewalk surface reflectance on air temperature and thermal comfort are evident in Gray Ball Thermometer (GGT) measurements. GGT only measures radiant heat that is particularly sensitive to humans. Cooler air temperatures are often associated with higher albedo surfaces, but higher reflectivity may increase the radiation load on pedestrians and increase thermal discomfort.

The relative difference between ambient temperature and GGT temperature is 4.87 ° C and 6.05 ° C. The larger temperature difference of the GGT confirms the additional radiant heat generated by the more reflective sidewalk surfaces and nearby thermal facades.