Foreword

Many new housing development projects are taking place on major transportation corridors. While it is logical to bring packed homes close to public transport, the provision of medium-density and high-density housing on busy roads will expose more people to traffic pollution. These developments often lack optimal design features to minimize their exposure. This is especially true for low, medium and high density residential developments in Sydney. According to current forecasts, Sydney will need to add 664,000 homes by 2036 to accommodate 1.6 million people.

A clear strategy to achieve this goal is to increase the stock of housing around transport corridors and railway hubs and to “accelerate new housing in designated fill areas”. Local councils seek to comply with state urban renewal goals and, more broadly, prioritize access to services, business districts and transportation corridors.

As a result, many rebuilt or updated sites are located near busy roads or train stations. Many government planning documents also include targets for a healthier built environment. Planning agencies across Australia have identified air quality and noise as issues of busy road development.

Measures to limit exposure

Suggested design measures include:

Building setbacks;

Connection or “stepping on” the facade of the building;

Avoid creating street canyons; and

Mitigation measures, such as greening close to the road.

New South Wales document proposal

Living areas, outdoor spaces and bedrooms should be located as far as possible from the main source of air pollution.

The policy also states that it is best not to use residential on busy roads unless it is part of a development project that includes adequate noise and air quality mitigation.

This is very gratifying. However, in many cases, these guidelines are not followed. It seems that seldom consider how resettlement, construction or planting can reduce the risks associated with transportation. In Sydney, you’ll see many new developments, balconies and large windows facing busy roads, or minimal setbacks, with little greening. Australia’s medium to high density living building practices can consider other designs, such as the inner courtyard area away from the road, as found in many European cities. The NSW guidelines even discuss what occupants should do “windows must remain closed”. A recent media report highlighted the fact that Sydney’s WestConnex project is expanding roads from four lanes to seven lanes (6,000 to 50,000 vehicles per day). The distance from the apartment building to the road will be reduced to 1.4 meters.

The contractor has been providing advice to residents on work to mitigate air pollution and noise. This includes the installation of air conditioning and soundproofing, as well as sealed vents. The size of a house built or remodeled in a subtropical climate must be kept closed and residents rely on mechanical ventilation, which is inconsistent with the principles of a healthy built environment.

How do we explain these planning decisions?

We are in a situation where the council can refuse to approve a beautifully designed, beautifully designed garage in front of a building, and people’s health is threatened by the priority of new housing development along the main road. How did we make this uncoordinated decision? Given the speed at which regeneration and major infrastructure projects are going on, this is a critical moment to rethink our urban space design.

Parramatta Road Corridor is an example of the current method. The city renewal project is highlighted on the state-owned Urban Growth NSW website, which is setting the agenda for Sydney’s urban transformation.

The Parramatta Road Corridor Planning and Design Guide contains useful advice on architectural design to minimize exposure to rail and road air pollution and noise. Although there are 21 pages devoted to noise and vibration issues, only three pages relate to air quality near busy roads. However, scientific evidence about the adverse health effects of air pollution may be more powerful than noise effects.

So what is the evidence?

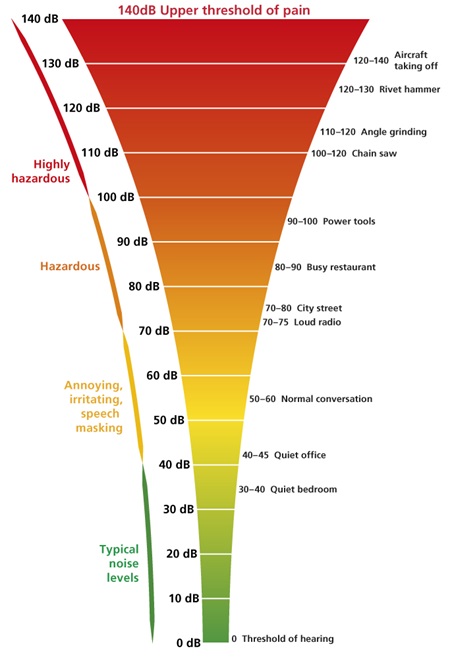

There is solid evidence that traffic-related air pollution is harmful to health. The concentration of various pollutants near the main road is the highest. We have shown that nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels are a good indicator of traffic-related air pollution after the construction of the Lane Cove tunnel in Sydney. After the tunnel was opened, the air pollution of the two main roads dropped to about 100 meters due to the decrease in traffic volume. At the same time, the level of nitrogen dioxide in the road near the tunnel entrance increases as the traffic volume increases.

Foreign studies have shown that the content of nitrogen dioxide and other pollutants decreases sharply with increasing road distance. NO2 pollution reaches a city level of 100-250 meters. The most serious decline was within 100 meters, although some studies documented the impact of major roads up to 500 meters away. The New South Wales Environmental Protection Agency estimates that road vehicle emissions inventory accounts for 61.8% of Sydney’s nitrogen oxide concentration. NOx is the main contaminant or precursor of NO2, which forms NO2 when NOx reacts with oxygen in the air. Adverse effects of NO2 exposure on health include all-cause, increased cardiovascular and respiratory mortality, admission to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, decreased lung function in children, and increased risk of respiratory symptoms such as asthma, stroke and lung cancer. Transportation – especially diesel vehicles – is also a major contributor to ultrafine particles in the ambient air. Roads and vehicles reach extremely high levels.

Although there is increasing evidence that ultrafine particles in animal and human toxicology studies have adverse effects on breathing and cardiovascular disease, epidemiological (population-based) studies are limited. Studies of short-term exposure have shown similar effects with larger particles – increased mortality and morbidity in respiratory and cardiovascular outcomes. However, the results are inconsistent. Vehicle emissions also have a major impact on air pollution. The health effects reported by the World Health Organization are similar to those of fine particulate matter and indicate that black carbon may be used as an additional indicator of ambient air.

The challenge is that although adverse health effects are attributed to black carbon and ultrafine particles, the expert’s position is that the evidence is insufficient to support the new standards for these pollutants.

Reducing pollution exposure should be a priority

As a public health practitioner, one can argue that evidence of the harmful effects of traffic-related air pollution is substantial and increasing. We should design a healthier building environment to avoid population exposure to traffic-related air pollution. Other options include Australia’s rapid adoption of more stringent fuel and vehicle emissions standards. Ultimately, reducing traffic and traffic congestion on major roads will reduce exposure. In the long run, this depends on providing better options for public and active transportation work and personal travel. Planning decisions to lay new homes on busy roads may undermine public health protection principles if left unchecked or not assessed.

https://theconversation.com/au/topics/traffic-pollution-6823