Foreword

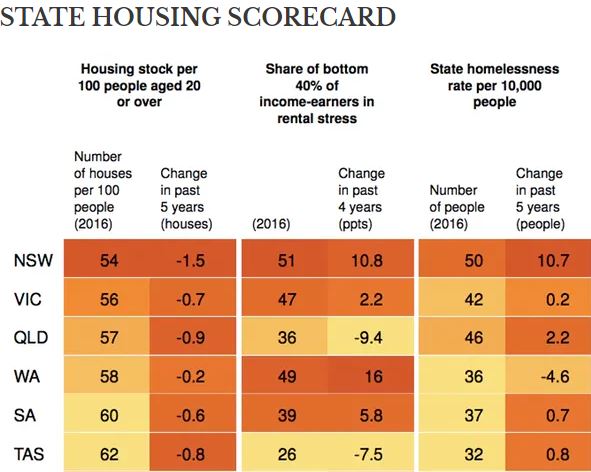

House prices may now fall, but Australians’ concerns about housing affordability have not eased. House prices in Sydney and Melbourne fell by a few percentage points, which is a cold comfort to first-time buyers. They still pay 50% more than five years ago. Prices may fall further, but even so, housing prices will remain lower than they were 20 years ago. Housing ownership in Australia is declining, especially among young people and the poor. In addition to Queensland and Tasmania, more and more low-income people in all states face rental pressures.

The required policy response remains the same. As the Glaton Institute’s 2018 State Orange Book shows, state governments need to ensure that more homes are built.

What happened to the housing?

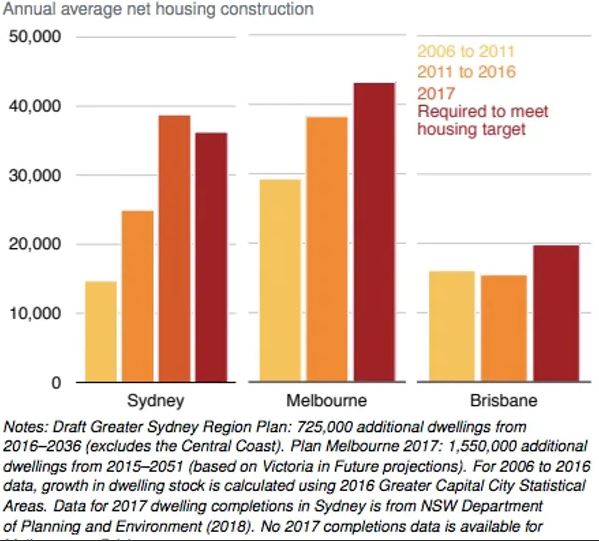

The population of Australia is growing rapidly. Our city has not kept up, so the per capita housing has decreased. The main obstacle seems to be the planning rules that delay or prevent development. With the exception of Tasmania, the per capita housing construction of all states has decreased compared to a decade ago. The New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland governments have changed planning rules and procedures over the past five years or so. Even with a large backlog of backlogs, this has led to new buildings eventually catching up with population growth.

Additional supplies have led to a flat rent in Brisbane and a drop in apartment prices. It will help push up rents and prices in Sydney and Melbourne. However, today’s record level of housing construction is the minimum required to meet the rapid population growth (mainly driven by immigration). However, authorities in New South Wales and Queensland are responding to NIMBY’s pressure by increasing the difficulty. In the Victorian campaign, Matthew Guy promised to do the same.

It is necessary to maintain a record of housing construction in order to achieve the housing goals of urban planning.

What should the government do?

Resisting high-density development is the wrong response. In order to build more houses in the inner and central suburbs of our largest cities, the state government should: introduce new regulations for small redevelopment houses. It will protect neighboring countries, reduce planning uncertainty and improve the quality of new developments. The code will include things that worry the neighbors most, such as privacy, height and opacity. In the main transport corridors and around the train station, four to eight storey high-rise buildings can be built “as is”.

Set housing goals for each local council. These goals should be linked to the development plans of the entire city. If the board fails to meet its program goals, it should be involved in an independent planning team. The best evidence is that an additional 50,000 homes per year in a decade could make Australia’s house prices 5-20% lower than the original price, which would exacerbate public concerns about housing affordability and promote economic growth.

Reforming lease rules

In addition to increasing supply, state governments should increase the attractiveness of rent by changing residential leasing laws to increase the safety of tenants and help tenants make their homes as home, making rents more attractive. The Victorian government has recently allocated more balance to tenants. Other state governments should follow suit. Of course, changing the leasing laws that benefit renters may reduce the supply of rental homes and increase rents, but any such effects may disappear very little. Some investors are more likely to sell their properties to first-time buyers, which means less renting and less renting.

The housing affordability crisis makes life difficult for low-income people. There are good reasons to provide additional public support to the most vulnerable Australians. However, not all policies are equally effective. Promoting social housing will be expensive. If you want to increase the stock of 100,000 homes (approximately enough to restore social housing to its historical share of total housing stock), you will need about $900 million in additional public funds or $10 billion to $15 billion in upfront capital each year. cost.

Even then, social housing can only accommodate one-third of Australia’s poorest 20% of the population. Most low-income Australians will remain in the private rental market. The biggest problem is that the “flow” of social housing is insufficient for people whose lives have deteriorated dramatically. Tenants usually take a long time to leave social housing. Most people have lived for more than five years. In order to overcome these problems, the government should build more social housing and closely target those who are at risk of homelessness for a long time. Otherwise, additional support for low-income housing costs should be provided primarily through increased federal rent assistance.

Stop providing false promises

The state government also needs to stop providing false promises. While policies such as the First Home Buyers Grant have repeatedly proven ineffective, they are at the heart of the housing plans announced last year in New South Wales and Victoria. Inevitably, these are actually the incentives for second home buyers: the biggest winners are those who already own homes and real estate developers who are ready to sell new homes.

Similarly, state governments should not claim that housing and commercial incentives and regional transportation projects transfer large numbers of people to the area. In the past, such policies have not changed much. And they provide an excuse for not making tough demands on the plan. Any policy proposed in the 2018 National Orange Book is not politically easy. But Australians need to face a harsh fact: either people accept higher density in the suburbs or their children will not be able to buy a house.