The Australian Art Gallery at Federation Square hangs John Bullock’s iconic portrait of Melbourne in the 1950s – Collins Street, 5 pm. This painting from work to the suburbs depicts a city full of people and architecture, but it is monochrome and flat. It has become iconic not only because it captured the consistency of the mid-20th century, but also because it represented the loss of a thriving dense city in the “wonderful Melbourne” of the late 19th century.

Although this era collapsed during the depression of the 1890s, Melbourne did not fall into decline, but fell into consistency and stability. Through decades of the early 20th century and two world wars, Melbourne remained a major city, but its development shifted to the suburbs.

As suburban shopping malls flourish, planners hand over the city to cars and parking lots, and retail activity in the central city has declined. For the demolition of a series of high-rise modernist projects, an important architectural heritage was threatened – in fact, it has lost a lot. The population of the central city is negligible, and Melbourne has become a rather boring place to close at night and on weekends.

While there are still many challenges, the transformation of Melbourne’s city centre since the 1980s has now become a global success story. This is not a story, but a lot: the design of new buildings and public spaces that are recycled from cars. From the water behind Melbourne has embraced the river and became a waterfront city.

Residents have become an important part of the city centre, while the inner city has become more dense, diverse and desirable. The city has become more green – literally, environmentally and politically. The university has been internationalized and their campus is urbanized.

Once filled with rubbish, the lanes are now filled with hips, housing and street art. Melbourne is always a refined city, and it is becoming a city with a profound character and urban buzz. The city is obvious, inexpressible and unfinished.

So how does transformation happen?

This is not a story about hero leaders or big projects, but a story of many agents and projects working together. While there are important forms of leadership and governance and major formal transformations, what really matters is the long-term slow incremental transformation.

A key issue in central cities in the 1980s was that few people lived there. Beginning with the Postcode 3000 program of the 1990s, the demand for accommodation is growing, so the challenge now is to prevent residential development from ruining the city and replacing other uses.

As the city becomes a place where people live, work, shop and play around the world, the concept of the Central Business District has been downgraded to history. The previous single-function areas became diversified; a city’s raw materials were mixed into rich curries.

Another shift is the expansion of public spaces and pedestrian-only areas. Although it can point to new open spaces, such as the Federation Square and the South Bank, most of this expansion is incremental.

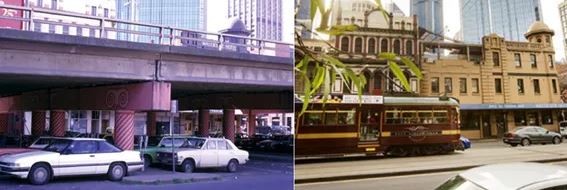

Recycling public space from a car is mainly a parking space or lane. This is a slow cycle: less available parking can cause people to switch from cars to public transportation; this in turn leads to more pedestrian life and more public space demand, which further contributes to fewer cars. Density complexity

One of the most obvious incremental changes is the overall increase in density – whether it is street life, residents, work or building volume. Density is one of the most difficult to manage urban properties.

On the one hand, the density is very good: it makes everything closer, so that we can visit more people and places on foot. However, density will also stifle the hustle and bustle of the city. Ultra-dense projects that disrupt nearby public spaces are destroying certain parts of Melbourne’s city centre.

It is no accident that the most vibrant laneway in the heart of Melbourne is located in an area below 10-12 floors. Excessive development of threats to the quality of public spaces remains a key challenge. The transformation of central city laneways from abandoned and dangerous wasteland to global tourist attractions is also gradual. Melbourne’s laneway appeared in the 19th century as an adaptation of the official grid. The blocks and diagrams were initially too large, and the need for subdivisions and shortcuts gradually led to the intricacies of the networks we inherited. In this regard, Melbourne is fortunate because most of its features are now reflected in the intersection of the official grid and the irregularities of the roadway. The potential of roadways has long been recognized, especially among young people and creative industries. Roadway renovation is more about making these activities flourish, rather than the various upgrades that are usually followed.

The danger now is that as the lanes become more upscale and “branded” global consumption, street art becomes proficient and real urban life continues.

City choreography, not micro management

Urban design in a complex city can be understood as an “urban arrangement” rather than a micro-management of urban forms or life, but a practice of frame, shepherding, support and restraint. How to strike a balance between over-regulation and containment of over-development and privatization, which would ruin creativity and productivity, and over-regulation would lead to over-development and privatization, leading to urban life? How to make the market flourish while controlling excessive development?

Good cities allow disordered, spontaneous, informal and unpredictable elements. Different people in the city, practice and architectural groups come together to form alliances; but different values, architectural forms and activities also cross and contradict each other, and thus create a more affluent society. We are all agents of choreography in urban life.

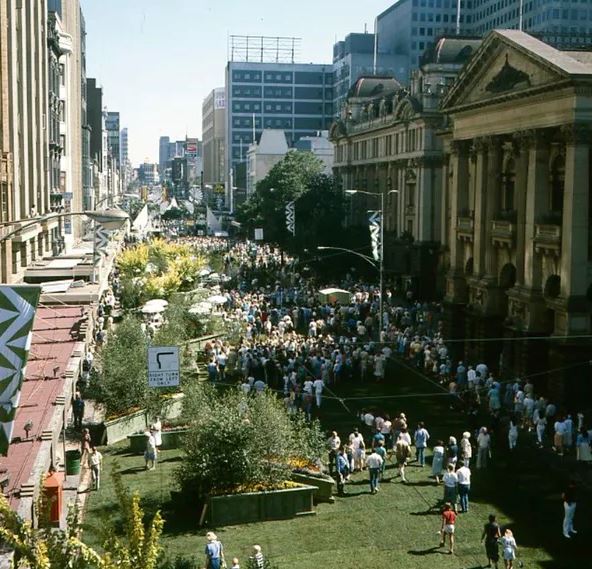

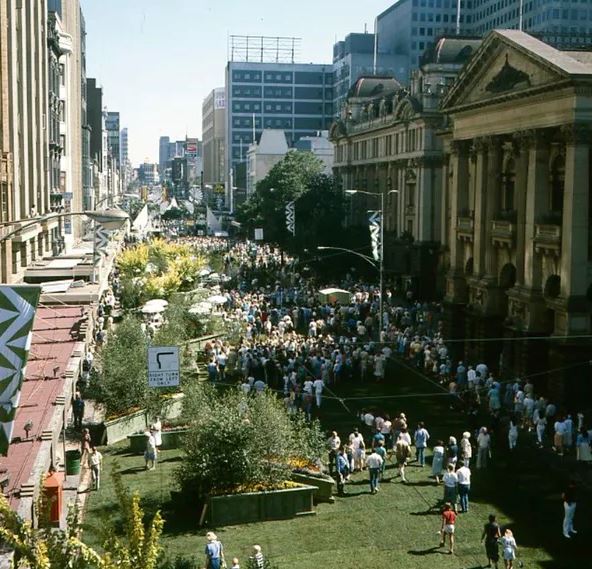

A major challenge in Melbourne is to develop a better relationship between the city and the country. In the 1980s, the state government played a key role in initiating a positive change and working with the Melbourne City Council to implement a series of urban design transformations – such as the South Coast strategy and roadway renaissance. Many Melbourneers will remember the greening of Swanston Street in 1985, when the state (by Evan Walker as Planning Director, David Yeken as head of department) laid the Civic Axis on the lawn and held a street The party has expanded our imagination of what it is. possible.

Since then, urban design in Melbourne has been booming, but state intervention in central cities (regardless of the ruling party) is often unaware of intelligence, authoritarianism and destructiveness. The recent decision to allow Apple to rename Federal Square and the anti-democratic approach to implementing Federation Square is just an example.

Where are we going from?

Any understanding of Central Melbourne today is also the basis for the next 30 years. If we compare many of the past visions of Melbourne’s city centre with the actual cities that emerge, we again find that incremental change is the standard for urban transformation. A bold vision may “inspire the blood of men,” as Bernum said, but rarely fully realized; real cities often become more complex and interesting. While the images of the idealized city’s future capture the imagination of the public, the deeper task is to understand the complexity of the city, drive its power, possible outcomes, and the interventions necessary to achieve them.

While there is always a new imaginative project and a place for immediate transformation, the key task in creating the future is to make imaginative modifications to existing cities. Although most of the changes are incremental, in general it is transformative.

The difference between Central Melbourne and all other Australian cities (actually most New World cities) is that it did not appear overnight. It has not been completed yet. Pay attention to this space.