Preface

The long-term impact of the coronavirus on our cities is difficult to predict, but one thing is certain: the city will not be depressed for too long. History shows that disease has a tremendous influence in shaping our cities. Regardless of the crisis, cities represent continuity – they can withstand, adapt and grow.

Once we regain our old life, we will most likely return to familiar routines, and the memory of lock-in and isolation will begin to disappear. Although our lack of memory can be said to be a resource of resilience, urban designers and planners have a long-term role in ensuring the health of urban life. In order to fight infectious diseases, cities need well-ventilated urban spaces and good sunlight exposure.

The design of these spaces (especially public open spaces) promotes different levels of sociality. Some spaces gather communities and are highly social. Others can be used as retreats in the city, where people drink coffee and read books for peace.

The performance of urban space during the outbreak of the disease now also requires our close attention.

What is urbanity?

Urban space is a place where communities gather. Urban planners and designers strive to create a sense of belonging, so that people can choose certain areas of the city, or even the city itself. Urbanity refers to the public life that occurs due to the exchange and communication of each space.

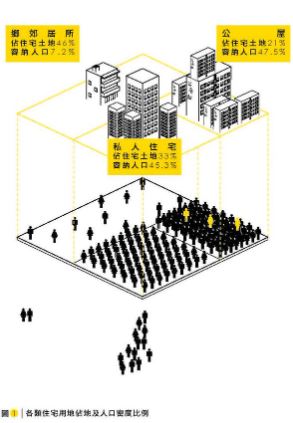

The combination of diversity and density achieves urbanization-it is the product of closely integrated social opportunities. This is why densification of cities is the goal of achieving healthy, social and prosperous cities.

However, the risk of spreading COVID-19 has increased. Therefore, it is worth remembering that only because cities with higher population densities can save money and improve infrastructure efficiency can it be possible to combat diseases such as sanitation. It is safe to complete the density correctly. It allows the interaction and connection between people we need, and we are now gone.

Once COVID-19 is no longer a threat, we will be eager to return to the past lifestyle as much as possible. Then, the role of urban planners and designers is to create a context for public life in a social and healthy way.

Disaster prevention

After the 2011 earthquake in Christchurch, New Zealand, about 800 buildings were lost in the CBD, and the community’s view of urban space is very different. The crowded areas and tall buildings are frightening. The common attitude is to avoid density-what if an earthquake occurs again?

Urban designers and decision makers understand that buildings and public places must respond differently. The safety pop-up area begins to appear. This new normality makes some old quiet cafes and public spaces resilient, while other pop-up windows become popular retreat areas. These urban retreats are far away from streets and high-rise buildings and therefore provide a way to “be there” and safe.

Both the earthquake and the coronavirus make people cautious about their safety in the city-because they are respectively close to surrounding buildings and other users of the space. Christchurch taught us a lesson about “united but separated from each other”: the city is not only composed of social spaces, but not all residents want the same thing.

People need to choose when using urban space to feel safe and secure. Larger social spaces are full of vitality and support public transportation and local economy, while urban retreat spaces apply the idea of prospects and refuges: they satisfy our psychological needs to observe and become public spaces (prospects), while feeling safe and Away from the scene (refuge).

Christchurch after the earthquake shows how the social characteristics and dynamics of urban spaces affect the people that these spaces attract and their behavior there.

Space design considering microclimate

Another factor to consider is the impact of the urban microclimate on the use and prosperity of public space.

The main activities of social spaces in large cities are based on human existence, social interaction and cultural exchanges. Compared with urban retreat spaces, the use and dynamics of these spaces are more predictable and consistent. Proximity to transportation or commercial use usually means that weather conditions have less impact on social activities and interactions.

However, when looking for peaceful experiences and personal space, people tend to choose urban retreat spaces. Here, they have a low tolerance for adverse conditions. This place itself is an attractive place, so the microclimate and personal comfort are important factors in using it.

Understanding, using and managing the microclimate, sunlight and ventilation is a clearly known way to fight disease and build safe and resilient urban spaces. People have long believed that it is important, but the way that people interact with the urban environment must be provided with choices, which has now become crucial.