OUTCOME 6

Melbourne is a sustainable and resilient city

This generation of Victorians has a responsibility to protect the state’s natural environment for future generations.

Victoria’s social, economic and environmental sustainability depends on the protection and conservation of Melbourne and the state’s biodiverse natural assets, or natural capital.

Melbourne’s Plan

Transition to a low-carbon city to enable Victoria to achieve its target of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050

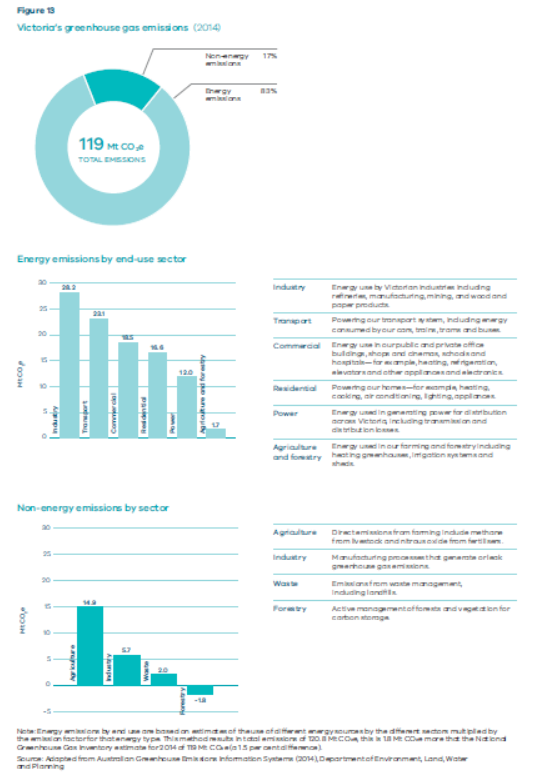

It is widely acknowledged internationally that major industrialised countries need to reduce carbon emissions substantially by mid-century to keep global temperature increases within two degrees Celsius. This is why Victoria has committed to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions to net zero emissions by 2050. Figure 13 shows the main sources of Victoria’s greenhouse gas emissions.

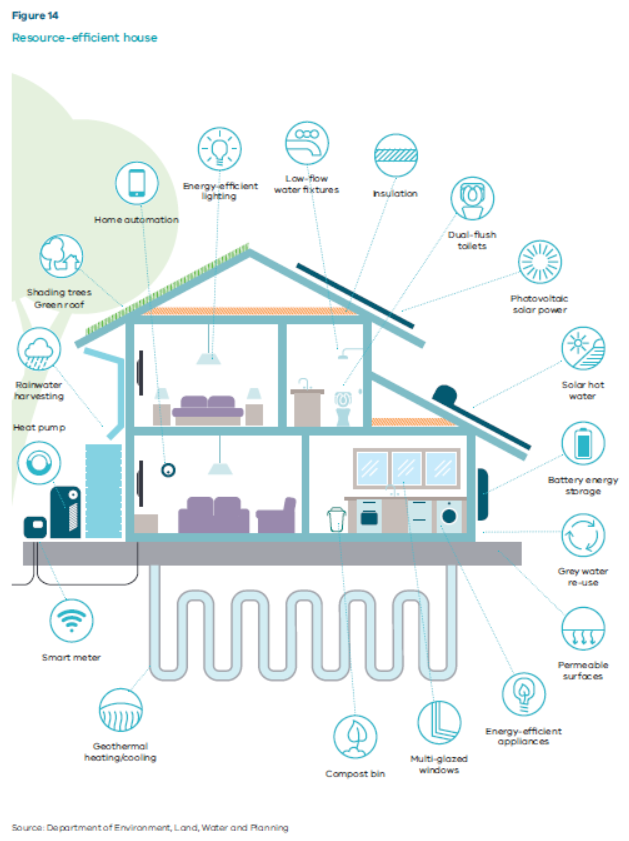

To transition to a low-carbon city, Melbourne must reduce energy demand, improve energy efficiency and increase the share of renewable energy. Victoria has set a target of deriving 25 per cent of electricity generated by renewable sources by 2020—with that figure to increase to 40 per cent by 2025. Melbourne has the knowledge, skills and technologies to meet its building energy needs in a sustainable way, using a range of renewable energy resources such as solar photovoltaic systems, solar hot water, geothermal and biogas. At a local level, greenhouse gas emissions from energy consumption can be reduced through precinct-scale initiatives that combine renewable energy and energy efficiency solutions.

To encourage a wider application of distributed energy technologies, Plan Melbourne will embed renewable energy and energy efficiency considerations in the land-use planning system and precinct structure planning process.

Reduce the likelihood and consequences of natural hazard events and adapt to climate change

There is a need to ensure that people, the environment and the city’s infrastructure are all prepared for the impacts of climate change. By working together, Melbourne can build its resilience to acute shocks and stressors, ensuring capacity of communities and the systems and structures that support them to adapt and grow.

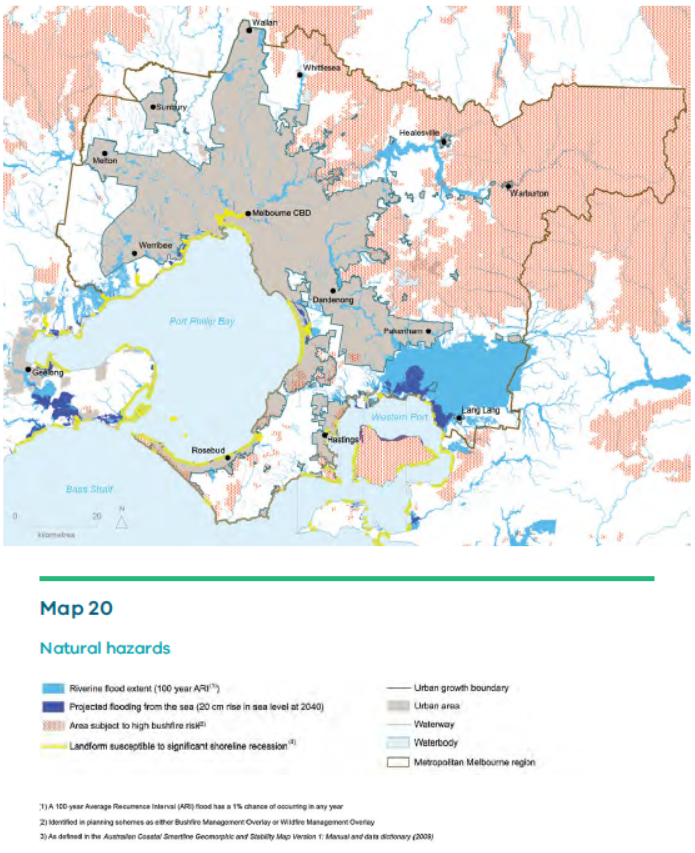

As Melbourne develops and populations increase, there is a risk that more people are likely to be exposed to natural hazards. Map 20 shows areas subject to key natural hazards.

Land-use planning and building provisions play a key role in reducing a community’s level of exposure to a natural hazard by influencing where and how development occurs. New development should be located away from extreme risks. Where risk is unavoidable, such as in existing settlements, land-use planning should reduce risk and ensure planning controls do not prevent risk-mitigation or risk-adaptation strategies from being implemented.

The approach set out in Plan Melbourne runs parallel with actions developed as part of Victoria’s second climate change adaptation plan and builds on the work of local government and emergency management agencies to build safer and more resilient communities.

Integrate urban development and water cycle management to support a resilient and liveable city

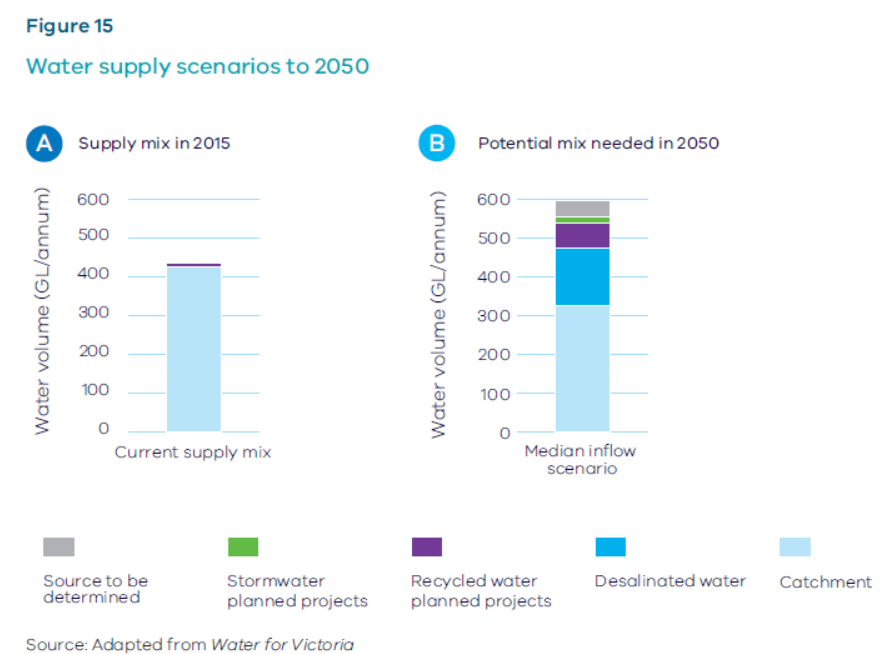

Plan Melbourne supports the implementation of Victoria’s water plan—Water for Victoria—by protecting water assets and influencing how development occurs across new and established urban areas.

Planning controls will be updated to require consideration of the whole water cycle early in the planning and design of new urban areas to improve the water performance of new buildings and precincts.

By considering the whole water cycle when planning for urban areas, we can improve wastewater management and recycling, support urban greening and cooling, protect waterways, minimise the impact of flooding and improve water security.

Make Melbourne cooler and greener

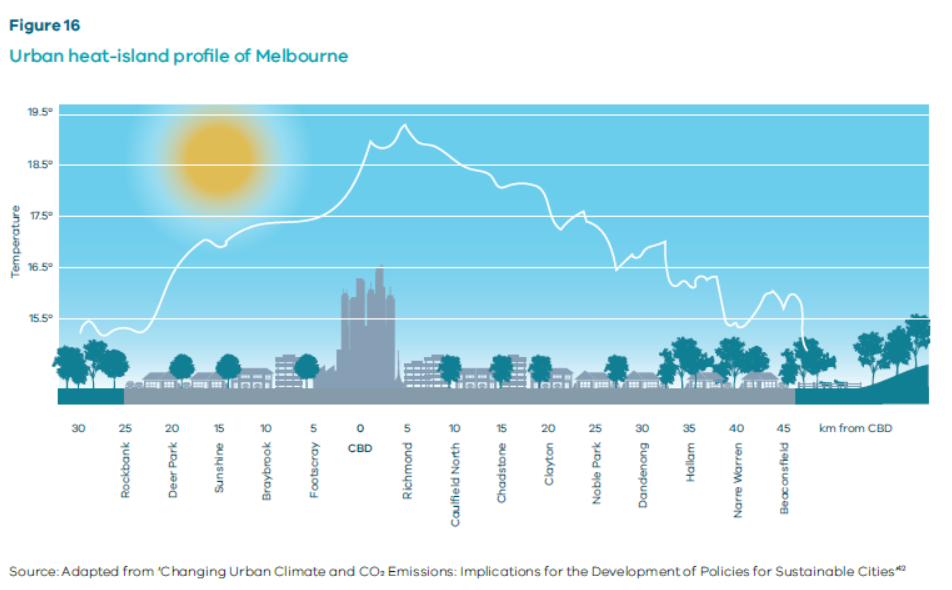

The urban heat-island effect is created by the built environment absorbing, trapping and, in some cases, directly emitting heat. This effect can cause urban areas to be up to four degrees Celsius hotter than surrounding non-urban areas.39 Figure 16 shows the urban heat-island profile of Melbourne.

Within the City of Melbourne alone, the urban heat-island effect is projected to result in health costs of $280 million by 2051.

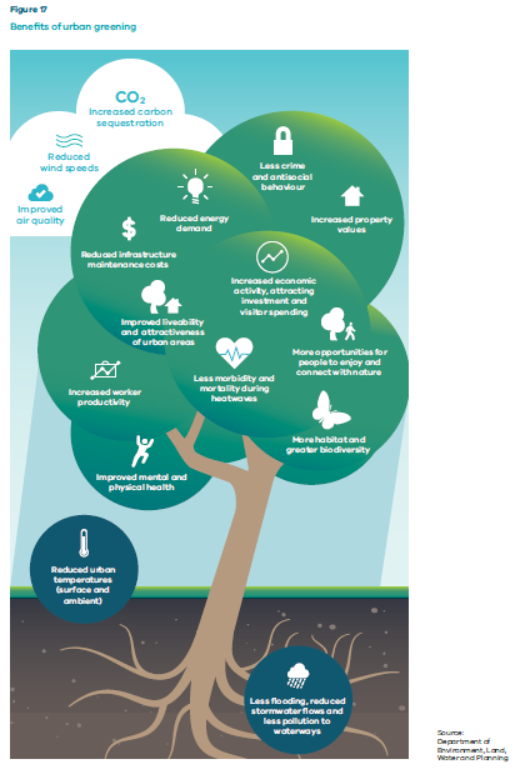

Urban intensification will add to the urban heat-island effect unless offsetting measures are implemented. Greening the city can provide cooling benefits and increase the community’s resilience to extreme heat events. Temperature decreases of between one degree Celsius and two degrees Celsius can have a significant impact on reducing heat-related morbidity and mortality. Figure 17 summarises the wide range of benefits provided by urban greening.

To mitigate the impacts of increased average temperatures, Melbourne needs to maintain and enhance its urban forest of trees and vegetation on properties, lining transport corridors, on public lands, and on roofs, facades and walls. Other methods of cooling the city include the use of special heat-reflective coatings for dark building surfaces to reduce the amount of heat absorbed.

Protect and restore natural habitats

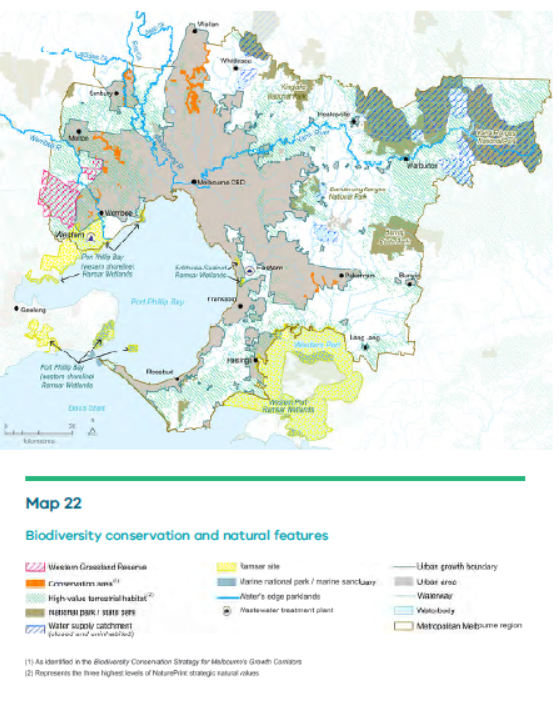

Melburnians are lucky to share their urban environment with an array of wildlife. However, as Melbourne grows, habitat loss and waterway degradation can pose a significant threat to native flora and fauna populations. As habitat becomes smaller and more fragmented through development, wildlife faces threats, such as lack of habitat to disperse to or barriers to dispersal.

There is a critical need to maintain and improve the overall extent and condition of natural habitats,

including waterways. Natural habitats need to better protect native flora and fauna, enhance the

community’s knowledge and acceptance of wildlife in areas they live, enhance access to nature and

recreational opportunities across urban areas and make Melbourne an attractive place to live and visit.

Map 22 shows Melbourne’s biodiversity conservation and natural features.

This direction should be read in conjunction with the Biodiversity Conservation Strategy for Melbourne’s Growth Corridors, which aims to manage the impacts of development for the next 30–40 years.

Improve air quality and reduce the impact of excessive noise

Melbourne’s air quality compares well with cities worldwide, but there are occasional days of poor air quality.

Air pollution is detrimental to human health, causing respiratory and cardiovascular disease and mortality, bronchitis, asthma, and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

It is estimated to account for more deaths than the nation’s road toll.

Children are particularly susceptible to air pollution because their lungs and immune system are still developing. The elderly are also more likely to be adversely affected by pollution.

The Environment Protection Act 1970 allows for the establishment of standards for the management of air pollution emissions and noise through state environment protection policies and waste management policies. These standards must be upheld. After all, air quality is as important to public health as safe food or clean drinking water.

Air quality and noise impacts should be a fundamental consideration in the design and assessment of all new developments.

Reduce waste and improve waste management and resource recovery

Waste management and resource recovery is an essential community service that protects the environment and public health and recovers valuable resources.

By 2042, it is projected that waste volumes in metropolitan Melbourne will grow by 63 per cent to 16.5 million tonnes a year.

Melbourne needs to reduce the amount of waste it produces by avoiding, re-using and recycling waste. Infrastructure also needs to be located to ensure waste management and recovery is timely, efficient and cost effective.

The recovery of valuable resources from waste will create jobs and add value to the Victorian economy. It is estimated that recycling employs 9.2 people for every 10,000 tonnes of waste processed, compared to 2.8 people when the same amount of waste is sent to landfill. Waste and resource recovery infrastructure planning must be effectively integrated with land-use planning to provide long-term certainty and to manage potential conflicts with incompatible nearby land uses.

Maintaining full operational capacity and output of waste and resource recovery facilities relies on a number of factors, such as securing and maintaining land separation distances. It is vital that facilities are sited, designed, built and operated to the highest standards so that the environment and public health benefits Victorians expect are achieved.

OUTCOME 7

Regional Victoria is productive, sustainable and supports jobs and economic growth

Regional Victoria will deliver choice and opportunity for all Victorians and help build effective networks to the global economy.

Victoria’s Plan

Invest in regional Victoria to support housing and economic growth

Investing in regional Victoria will support housing and economic growth and bring significant social and lifestyle benefits to regional communities. The Victorian Government will:

• work with the nine Regional Partnerships and local governments to support the growth of housing and employment in regional cities and towns

• ensure the right infrastructure and services are available to support the growth and competitiveness of regional and rural industries and their access to global markets.

Improve connections between cities and regions

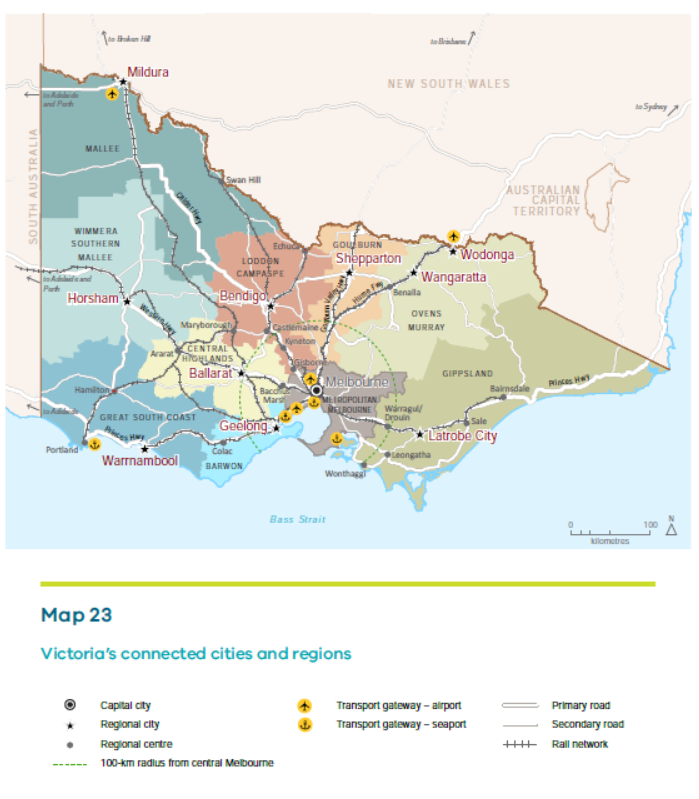

Regional cities and towns need to be connected by efficient and safe road and rail transport corridors. Strong links, both within the regions to major hub destinations as well as back to Melbourne, make it easier to live and do business in regional areas.

Better public transport connections (including rail, long-distance coach, and school and town buses) are critical for the movement of people to jobs and services. The Regional Network Development Plan is the Victorian Government’s long-term plan for transport investment in regional Victoria. It will deliver a modern commuter-style service for the growth areas of Geelong, Bendigo, Ballarat, Seymour and Traralgon, and service improvements to outer regional areas.

Victoria’s freight task is projected to triple by 2050—much of it is destined for Melbourne or export. Infrastructure that connects rural producers to state-significant corridors—as well as the Port of Melbourne, Melbourne Airport and other regional ports—must be improved to support the economies of regional cities and regional industries.

Digital connectivity is fundamental to business and jobs growth and critical for accessing services. In particular, the health and education sectors highlight the potential of providing services online.