Santana Row is located in the heart of Silicon Valley and covers 42 acres. Its dense high-end retail, residential, restaurant and office created a city center. The building – with earthy tones and pastel stucco with urban moving houses – clearly evokes old Europe, and the developer introduces antique metalwork, pottery and stone fountains to further instill a sense of history (a store or even an import The 19th century facade of French architecture). Meet the fashionable people in the shopping center, the new urbanism cousin: “Lifestyle Center.”

This form is becoming more popular among developers and shoppers. But while the Lifestyle Center is promoted as a 21st century, community-oriented alternative to the unintentional shopping center, they claim that the street “authenticity” may be a new type of retail façade.

shopping center

The Lifestyle Center is defined by the International Council of Shopping Centers (ICSC) as a “professional center” with “a high-end national chain store that provides dining and entertainment in an outdoor environment.” ICSC further described it as “multi-purpose” leisure time. Destinations, including restaurants, entertainment venues, design ambiances and facilities for convenient leisure browsing such as fountains and street furniture. ”

This description sounds a lot like a shopping center. But there are obvious differences. Traditionally, large shopping centers have been fixed by department stores Lord & Taylor, Sears, while life centers have been fixed by large specialty stores (Pottery Barn, Crate & Barrel, Williams-Sonoma) or cinemas. The regional mall has an average retail space of 800,000 square feet, while the living center is smaller, about 320,000 square feet.

Over the past 15 years, these centers have risen in affluent suburbs across the country, and they are often mixed-use developments that bring apartments, apartments, restaurants, cinemas, grocery stores (and even hotels) to the history of shopping centers. On a single retail center. The ICSC estimates that there are 412 life centers in the United States today (only less than 2% of the total number of shopping centers). At the same time, some shopping centers, such as the Biltmore Plaza Shopping Center in Asheville, North Carolina, have even taken radical steps to tear the roof into pieces.

Attention to detail

Michael Beyard of the Urban Land Institute (ULI) believes that the lifestyle center is designed to transform from a “wow” building to a “comfortable building”. According to Beyard, developers are trading high-rise malls or American malls. The roller coaster makes the living center pay more attention to detail: cobblestone sidewalks, cast iron lighting or art deco neon lights.

At the Market Clarendon Market in Arlington, Virginia (completed in 2001), developers spent more money on signs, sidewalks, facades, plants, fountains and sidewalks. However, the price tag for these additional features is a wash-and-buy: the developer does not need to build the roof of the mall, saving a lot of resources.

Robert Koup of Jacobs Engineering explained that the architecture of the Center of Life is deliberately “eclectic” to make it “legitimate.” He said developers need to ask architects to respond to a specific timeframe architecture or use multiple architects in a single project. For example, the San Francisco BAR Architects who worked on two blocks in Santana Row described their “senior loft and retail building…modeled at the turn of the century”, all designed to “recall historic shopping.” place”. By integrating historical elements into retail projects, “Lifestyle Centers are designed to make them look and evolve over time,” continues Koup. The mix of buildings also provides a solution to another criticism of shopping centers: their homogeneity in form and retail. This is a compromise antidote to complaints about the sterility and identity of chain stores. Indeed, because lifestyle centers are dominated by chain stores (like their former mall brothers), the quirky style makes them look more unique, localized and unlike chain stores.

This is one of the highlights of the lifestyle center: it imagines the picturesque streets that have been preserved in the past, but they all start from scratch. Of course, some people may be ironic about the true sex of manufacturing.

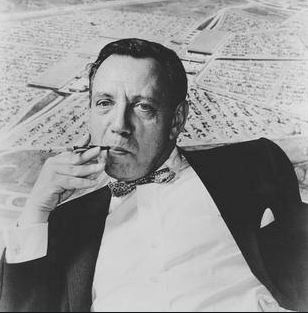

Has Victor Gruen’s vision been fulfilled?

In many ways, the Lifestyle Center is trying to realize the grand vision of Victor Gruen, a pioneer in the 1950s. Gruen, a Jewish architect from Vienna, moved to Beverly Hills, where he promised that the mall would bring a sense of urbanity to the “pretending respectable and boring” of the post-war suburbs. Although it is hard to imagine now that when the suburban shopping centre first opened in the 1950s, contemporary observers compared them to the most famous retail experience of the time: the city centre. The first shopping center in Gruen – the Southdal e Center built in 1956 in the suburbs of Minneapolis – most people think that Gruen has successfully brought the city center to the suburbs. “Architectural Records” said that Southdale “is more like the urban area than the urban area itself.”

The main attraction of the mall is its commercial density, pedestrian space, cafes and art (now seemingly man-made), which provides an urban atmosphere for the new suburbs who have just left the city. Gruen boasted that he recreated the “Ancient Greek Market, the Medieval Market Square and our own town square” with his Southdal e Center. In apartment buildings, retail has become the main focus of suburban shopping centers. Many of Gruen’s low-profit plans eventually appeared in the locker room. Southdal e sits in the middle of the parking lot and is largely isolated from the surrounding community, forming a huge retail island. Even Gruen admits that all “trees and flowers, music, fountains, sculptures and murals” are designed to increase profits. Or as he wrote, “The environment should be so attractive, customers can enjoy a shopping trip… this will make the cash register sound more bells and achieve higher sales.” Still, Southal e achieved immediate success: on the first day of the opening, 75,000 customer visitors stopped to watch the new phenomenon. The grand design of the mall proves that suburban residents may be tempted to stay in climate-controlled private spaces for hours during hours of shopping, creating a new US retail model.

Different flavors of the same thing

Suburban shopping centers (which are always surrounded by asphalt parking lots) that have always focused on blank faces for decades have become a feature of post-war retail models. In the process, large shopping malls stole the market share, taxes, jobs and limelights of traditional urban shopping districts.

However, the mall was ultimately doomed to failure due to its own success: the formula became too easy to replicate, and the design was everywhere. The mall has the same chain of stores and a one-size-fits-all design that symbolizes the homogeneity of numbness and the loss of the community.

“People suddenly realized that this shopping mall formula is everywhere and more and more boring,” Biade said. The sheer size of many shopping malls may also overwhelm shoppers. For example, Pennsylvania’s 2.4 million-square-foot King of Prussia Mall has more than 400 stores; it is positioned by Nordstrom, Macy’s, Bloomingdale’s, Neiman Marcus, Lord & Taylor, JC Penney and Dick’s Sporting Goods.

The Lifestyle Center recommends correcting this numbing situation. However, Cooper Carry architect David Kitchens expressed doubts about their longevity. He said: “They are a better, fresher mousetrap that can work for a while and then disappear.” He didn’t establish a true connection with the surrounding community, but rather considered many of them (especially those specializing in retail “The people of the industry” “designed as a category killer, will draw lifeline from everything.”

Kitchens insists that the transition from a large shopping mall to a smaller lifestyle center is part of a larger story. He believes that the Lifestyle Center is taking advantage of Americans’ “renewing the emotional aspirations of the community.” He continued: “As development grows, people now want to decentralize management and reintegrate personal feelings into life.” These new retail centers see themselves as the main streets of the past, hoping to reproduce from the 1950s to the 1990s. Eage to cover the US boom with large shopping centers. However, Glenn’s ideal shopping center and the new urbanist lifestyle center have the same ambition at their core: a thriving community center, yes, but ultimately it will bring considerable profits.

Whether we like it or not, suburban Americans have been building communities on the basis of commercialism for nearly six decades.