The Internet has reached our city. Smart cities are optimized for efficiency, productivity and comfort.

Smart cities use intelligent transportation systems. It is managed by a comprehensive urban command center that analyzes the ubiquitous raw material in the digital age: big data. With the daily lives of citizens, they leave traces of data everywhere, even in the sewers.

Many technology companies and city governments are praising the new situation in smart city research: urban scientists who eventually impose strict scientific (ie positivism) ideas on urban governance. However, Jeremy Kun confirmed: Quantification cannot resist prejudice.

Commentators such as Cat Matson, Charles Landry and Paul Mason advocate a human-centered approach to urban design. In our own work, we warn that ignoring decades of research by architects, geographers, urban planners, designers, and sociologists may lead to a dystopian future if we desperately pursue convenience And efficiency, people will lose their agency.

Algorithm culture

Big data needs to be analyzed through algorithms to generate filter bubbles. Companies like Facebook and Google have deployed complex algorithms to help us deal with otherwise swollen social media. Select the content displayed on the Facebook news feed based on the user’s profile, location, interests, and online habits (what they post, share, recommend, and “like”).

The popularity of social media stems from its ability to create personalized spaces, walled gardens, which can be tailored to personal preferences and prefer content that is relevant to each user. A proprietary algorithm determines what is considered relevant.

There is no sense of ethics. It is these algorithms that determine the composition of Facebook news feeds, Google’s top search results, and recommendations for who to follow on Twitter and what to buy on Amazon. They are optimized to prioritize content that generates more business.

Diversified advantages of the city

As more and more social media platforms use urban environments as their playgrounds, this algorithmic culture has important implications for cities.

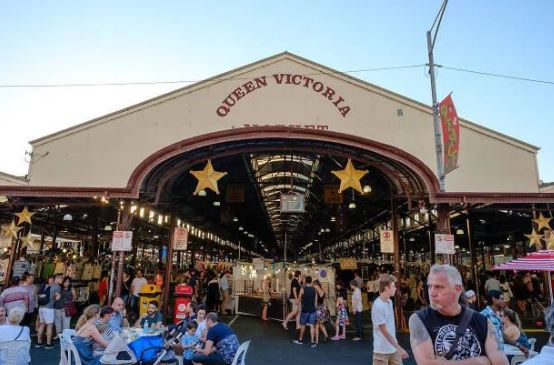

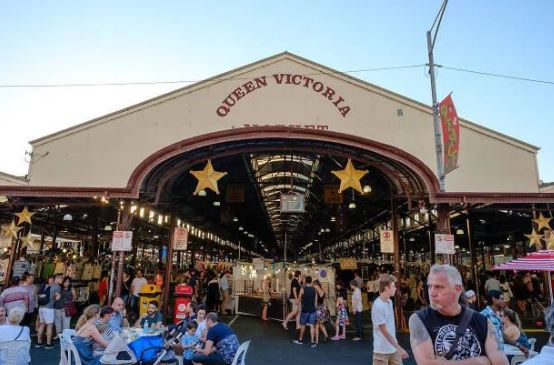

People gather in cities not only because of the infrastructure and convenience they provide, but also because they provide choices. Cities are fundamentally about possibility, opportunity and diversity.

Jane Jacobs pointed out:

The city can provide something for everyone because it can only do so if everyone has created the city.

Ethan Zuckerman believes that the city is the engine of chance:

By placing various people and things in a confined place, we increase the chance of accidentally discovering unexpected events.

However, Zuckerman also asked: Does the city really work in this way?

For smart cities controlled by big data and algorithm analysis, this is a timely question. How does a smart city become an unexpected engine? Can we design a lost smart city?

Here are some examples of why this might not be a bad idea.

Get lost and meet strangers

Public transportation travel planners usually optimize for two factors: the fastest speed and the shortest distance to get you from A to B. However, there are many opportunities beyond telematics.

Why don’t we choose to take the slow road, the least polluting route to work or the scenic route home?

Experimental prototypes such as Martin Traunmueller’s Likeways and Mark Shepard’s Serendipitor can make you lose yourself and rediscover your city.

In addition to various places, the city also provides a variety of things for people. However, we often stay in our existing friendly and convenient social network. Eric Paulos’ “Stranger Stranger Project” investigates anxiety, comfort, and entertainment in public places.

However, our ability to unleash the advantages of urban social diversity is still in its infancy. Early examples include co-working spaces and gathering groups that bring together different people, airlines that provide social seating, and design ideas (such as jukeboxes) to enhance play and curiosity.