Foreword

The planning of the colonial colonial countries has always been carried out on the land of the indigenous people. Although indigenous rights, identity and cultural values are increasingly being discussed in planning, their mainstream accounts actually ignore the assumptions of the discipline, the colonization of technology and methods, and the legacy. This groundbreaking book reveals the empire origins of Australian settlers-colonial countries in planning classics, professions and practices.

By documenting the role of planning in the history of Australia’s relationship with indigenous people, the book portrays the lasting effects of colonization. It provides a new historical record of colonial planning practices and rewrites the urban planning history of major Australian cities. Modern land rights, indigenous property rights and cultural heritage frameworks are analysed according to their critical importance to today’s planning practices, with detailed case descriptions. In rebuilding Australia’s plan from a postcolonial perspective, the book broke the orthodox narrative and revised the story that the plan has told itself for more than 100 years. New approaches to Australian indigenous thinking and practice planning have progressed.

Marginalization of indigenous peoples

This is the sixth article in our series, “The City for Everyone,” which explores how members of different communities experience and shape our cities and how we create better public spaces for everyone.

Nearly 80% of Australia’s indigenous and Torres Strait Islander people live in urban areas, but cities often exclude them and are marginalized.

Urban planning and policy are critical to this and can be seen at critical moments and processes that affect the Australian urban environment.

Today, the indigenous people continue to be seen as “out of date” in the city. Their rights and interests are essentially intangible in urban history, policy and planning practices.

In order to correct the unequal status of indigenous people in our cities and to strive to achieve urban land justice, we need to consider the planning process that leads to the marginalization of indigenous people in the history of Australia.

Planning isolation and assimilation

For a long time, planning has always believed that social issues can be solved through spatial organization and design. This is an activity that has taken place even before the “planning” profession appeared in the 20th century.

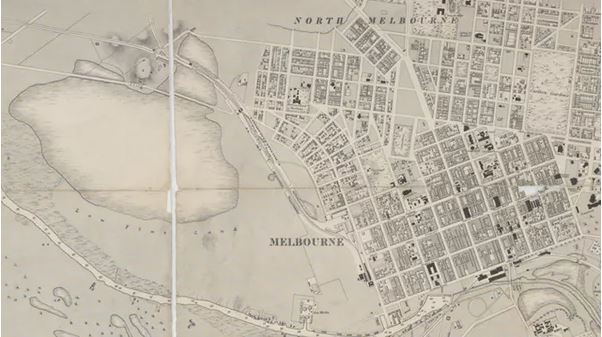

The earliest activities of the Australian solution rejected the indigenous law and governance system. Colonial agents such as surveyors, cartographers, protectors and governors attempt to remove people from developing towns. They use maps, regions and borders to control the movements of the indigenous people and symbolically erase their connection to the landscape.

The population is based on apartheid because of the establishment of small indigenous protected areas, allegedly for the “protection and civilization” of indigenous people. As the expanding cities consume more land and become more dense, the anxiety of whites threatening the disease increases.

But these concerns did not take into account the living conditions of the indigenous peoples. Native people are considered a “threat” to public health. In the minds of officials, this requires containment and surveillance of reserves, which are pushed away from urban areas, become smaller and more easily overlooked.

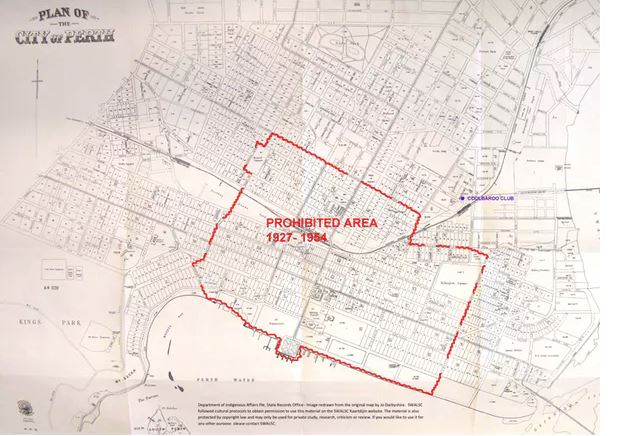

Develop town boundaries and set curfews to regulate when and where people use urban space. These are widely adopted practices. In Brisbane, Darwin, Perth and Broome, for decades, borders have been used to control the movements of indigenous peoples as well as economic and social opportunities. These practices extend to the 20th century.

As Australia’s indigenous policy shifts from apartheid to assimilation, the plan reflects and implements this change. Reserves close to the town have been closed and sold. The Coranderrk Reserve near Melbourne was closed in 1924. In the 1950s, the Kahlin compound in Darwin was closed and its population moved to the farther Bagot reserve.

Indigenous people were forced to leave these isolated areas and return to urban areas. The inner city suburbs, such as Sydney’s Redfern and Melbourne’s Fitzroy, are important venues for maintaining social and political communities.

These inner cities and communities have swept through the broader urban renewal agenda to rebuild the city by rezoning and providing new public housing. This is seen as a way to address poverty.

However, as reported in the Bringing Them Home 1997:

Providing public housing for indigenous families causes them to clash with government authorities, thereby increasing the risk of raising children. For example, strictly limit the number of visitors who live in public housing and limit the number of family members who can live together, regardless of the relationship between the indigenous family and the community.

Urban policies and planning continue to make people think that indigenous people have no real place in urban areas.

However, these discriminatory policies and practices have not been challenged by indigenous peoples. Although it is still difficult to achieve land justice in the traditional urbanized indigenous peoples of traditional countries, in the face of these challenges, innovative solutions are being sought.

Going to urban land justice

The ongoing leadership initiatives today show how the community can re-plan to achieve its aspirations. A land use agreement negotiated by Yawuru indigenous property rights holders in the Broome area provides a framework for local visions for commercial and residential development in recycling and utilization planning. Earth Building Design Victoria is leading a new approach to planning and designing the built environment. In the planning profession, this key issue has begun to receive more attention. The Queensland Government has passed legislation recognizing that planning should focus on protecting and promoting the knowledge, values and traditions of indigenous and Torres Strait Islander people.

The Australian Planning Institute adopted an education policy in 2016 that requires all accredited higher education planning degrees to address the relationship between indigenous people and planning. This requires teachers and students to participate more deeply in the history, theory and ethics of the profession. These are welcome early steps.

In the long run, promoting a truly just relationship between planning and indigenous people means sharing the right to shape the process of urban development and determining what the problem is and what value it is. Planning thinking, methods, methods and practices must continue to shift to support this desire.