Although the parking lot is a negotiating facility for the baby boomers, it is an eye for millennials and up-and-coming newcomers. A new generation wants more cities and fewer cars. Abandoned parking lots are the latest trend in urban planning on a global scale.

Between 2010 and 2015, Philadelphia removed 3,000 off-street parking spaces from the city centre. Copenhagen is also taking the same path. Zurich implemented a citywide ceiling to limit parking spaces to the 1990s.

Amsterdam announced that it will dismantle parking spaces at a rate of 1,500 per year. The city’s goal in 2025 is to eliminate more than 11,000 parking spaces from the street, providing space for cycling.

San Francisco and New York have adopted the concept of “small parks.” These are mini parks or outdoor cafe lounges that temporarily replace several parking spaces during periods of low demand.

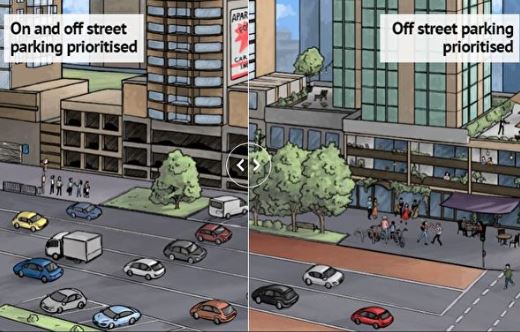

The theory holds that as parking volumes decrease, the attraction of driving gives way to more environmentally friendly modes of transportation such as walking, cycling, riding, car sharing and public transportation.

Some evidence suggests that reducing or limiting parking can be rewarded. In cities where these measures are implemented, driving has declined and the use of public transportation has increased.

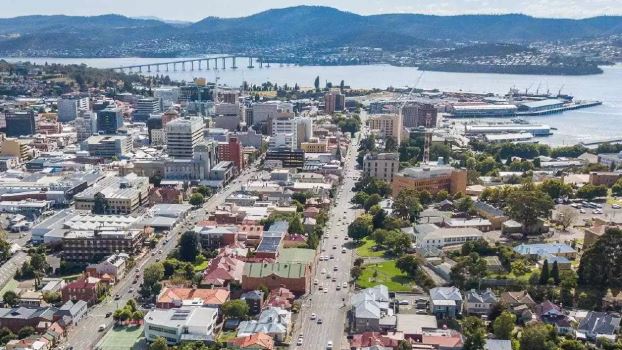

What happened in Australia

In Australia’s largest city, Brisbane seems to be regressing. The Courier Mail recently published a report:

The suburban streets of Brisbane’s two suburbs have become full-day parking because new residents of the apartment are forced to use on-street parking.

In response to this sentiment, the Brisbane City Council proposes to increase the number of parking spaces required for future apartment buildings in the middle and outer suburbs. The increase in parking is designed to increase the quality of life and safety in the suburbs of Brisbane.

Unfortunately, Brisbane did not track existing residential parking spaces. This lack of clarity creates an imbalance in parking supply and provides an opportunity to share the parking economy. Operators such as Parkhound and CURB can allow residents to rent unused parking lots, while neighbors can use the public supply of on-street parking.

At the same time, Sydney has officially announced “climate emergency”, following the leading position of global cities, including New York, London (and the entire UK), Auckland and Vancouver (followed by Canada). Although welcomed by environmentalists, the statement is not firmly committed to reducing driving or parking.

Similarly, in Melbourne, outside the CBD – there are plans to reduce parking – there are many free, largely unmanaged on-street parking. Residents usually think they have the right to use this parking space.

Obviously, Australian cities are caught in the old-fashioned “predictive and providing” parking supply model. The model relies on the idea that if each site provides space for all residents, employees, customers and visitors during peak demand periods, there will always be enough parking spaces.

While this approach may be applicable in the post-war period, it is not feasible for today’s growing, crowded and warming cities. The challenge for planners is how to accommodate more and more urban residents at a reasonable distance from work and facilities. There is not enough car space in the city – whether it is moving or parking.

Is there a better way

of course. Some cities have begun setting maximum parking standards. In other words, the city has a cap on how many parking lots can be provided for a particular project. Sometimes these supplement the minimum parking requirements; in other cases, the latter are eliminated.

The sale of parking spaces separately from the housing unit, known as the “split”, is another popular policy. It ensures that the true cost of car storage is transparent rather than hidden. This means that no car or bicycle family does not have to pay for the parking fees they don’t need.

Some developers are providing car sharing space for new buildings, rather than individual parking lots.

Some employers offer parking “cash spending” options – employees can get paid for parking spaces. Employers who continue to provide parking fees every day instead of monthly to avoid “sinking costs” – paying parking fees, employees want to get their money.

Other useful (but almost no new) planning concepts include “30-minute city” and “transit-oriented development”. These methods help reduce the need for driving and parking by centralizing public transportation sites and the use of people and land around the corridors.

Will reducing space lead to a shortage of parking?

People are often worried that if parking is reduced or restricted, this will result in a parking shortage. This can be avoided if parking is considered a key component of the urban transport system and coordinated with other elements.

Australian cities need to develop comprehensive parking strategies at the metropolitan level. These strategies must be combined with general transportation and land use plans. Unfortunately, this is often difficult to achieve because state governments are usually responsible for planning and building transportation systems, while local governments are responsible for parking.

The impact of reduced parking on urban residents needs to be offset by providing higher quality and quantity of public and active traffic. This requires substantial investment in public and active transportation.