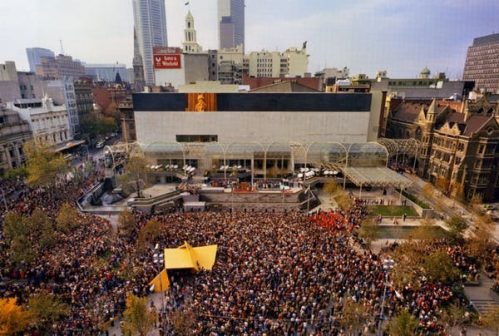

For 150 years, Melbourne people have dreamed of becoming a square, a great ritual space where people can relax, celebrate, protest or simply enjoy companionship with their fellow citizens. They have a word about their dreams – a citizen square. The term “citizen” means “city” or “belonging to citizenship”. They don’t want markets, parks, arenas or shopping centers – there are many in Melbourne – but people meet and celebrate the grand square of citizenship. This will be a market or forum in Melbourne, a place to talk, relax and celebrate rather than commerce. In 2000, after decades of imagination, planning, debate and lobbying, dreams come true. As we now say, the Federal Reserve Square is not a traditional European public square, but a clever combination of squares and winter gardens in a quirky postmodern style. People like it. The Federal Reserve Square is a small miracle, and a new public asset has won the tide of privatization.

“Melbourne does not have a large central square,” he exclaimed. The best location between Collins, Swanston and Elizabeth Street opposite the City Hall has been privatized, and buying it will cost “a pretty amazing amount”. However, for the object of “the supreme importance of this supremacy”, he believes that “this money will be spent very well.” With the advent of the gold rush, the cost of recycling a site has soared to an unachievable goal. This dream only came back in the 1920s, when the City Councillors debated the plan to build a square in the eastern market of Burke Street. In 1929, the Metropolitan Planning Commission recommended a “spacious city square” next to the new town hall at the top of Burke Street opposite the parliament building. Such a complex “dedication to the city’s ritual, artistic and administrative activities” will enhance “community pride”. Artists and writers influenced by European experience also called on the square as an antidote to Melbourne’s notorious Puritanism. In 1935, artist Norman Lindsay announced: Public squares, the surrounding cafes and orchestras, the fun of the promenade, the cheapest, the cheapest refreshments, are great at all times – when these are rejected, people have little to do but sprint for the bar, frequent The cinema or the bunny returned to his home.

The new citizen idealism after the war once again sparked interest in the Civic Square. At the top of Bourke Street, the square above the Swanston Street and Flinders Street railroads was unveiled and controversial – and shelved. Keith Dunstan, a favorite but skeptical observer of the Melbourne scene, ridiculed “Melbourne’s Square Dance.”

Business delivery failure

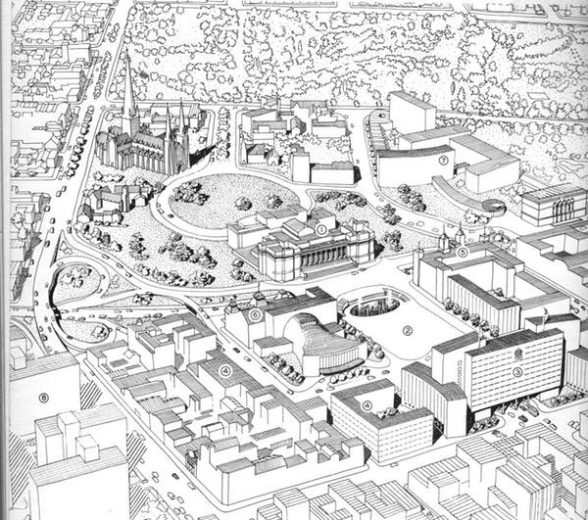

In the 1960s, retailers joined the business as shoppers moved to suburban shopping centers. They believe that a city square will make the city center more vivid and keep a “doughnut city” threat – a death center surrounded by a lively suburb – in the bay. Through the “external” interest of city traders, the idea that the square may pay for itself introduces a new set of expectations in the public debate. People began to talk about “city squares” instead of “citizen squares.” The idea of a square that can recover costs has attracted civic leaders and city businessmen. When Melbourne finally got a square in the early 1980s, it was like a mix of “citizen” spaces, becoming the front yard of an international hotel. The committee purchased a narrow strip of land on Swanston Street between St. Paul’s Cathedral and the City Hall, split it in half, sold a portion to the hotel, and kept the other part as a little-known “square”. . It is neither a fish nor a chicken, it never really works. It is paralyzed by compromise.

The people who designed and managed the Federation Square seemed to have noticed the lessons of failure. This space is generous and inspiring because the old square is narrow and miserable. I was very interested in the arrangements to ensure public access for community groups and political protesters. They seem to be managed in an impressive, non-partisan manner. From the outset, there are expectations that restaurants and bars will be served alongside public institutions such as the National Gallery of Art (NGV), the Australian Mobile Imaging Center (ACMI) and SBS, which is the main space. And other commercial activities to complement the nature of its citizens. However, the square’s citizenship and cultural charter has been carefully crafted to ensure that citizen values predominate. When I read it, I was reassured by the repeated use of words such as “public”, “citizen” and “meeting place”. I am content to the requirement that any business activity must be linked to the purpose of its primary (cultural) user and to be subordinate to the “citizen and culture” characteristics of the entire square.

Other views

The views held by romanticism are still practical today. Today, technological globalization and the development of civilization have reached a critical period. If we try to understand our times and our lives and what we are doing, we must think in a holistic way. The current city is a complex system in a constantly changing state. Change is the essence of the urban system. Reform and replacement of things no longer have obvious boundaries. Nothing is immutable. Nothing is static or simply linear. Therefore, planning must be flexible enough to accommodate these changes,

For the streets & plazas & buildings & open spaces & ecosystems (these places where people live & work & meet & socialize and retreat, they must adapt to the changes that occur automatically and meet the needs of people. A sense of direction # Various possibilities for change and growth must be raised at the planning level. Planning should not only consider sensory stimuli & beauty and change, but also pay attention to direction and identifiability. Planning should be realized from the past. The transformation of transsexuality into multiple possibilities, and its changes in the future will also bring about the function of urban open space and the way we experience open space. The future open space must be regarded as an eternal stronghold*, one inside the city. A place that reflects the stability and calm of our lives as a whole. If the pace of action of planners is consistent with the times, planning and designing open spaces in a clear language can provide the urban residents who have lost So things, our city will become more suitable for living, and people can find a real need to meet them. s home.