Science clearly shows that the world is turning to a more unstable climate. Weather events such as flash floods in Sydney last week will be more frequent and extreme, and the gap between them will become shorter. As sea levels rise and frequent floods, water features will become part of our city’s daily lives.

Most Australian cities are already located along coastlines or river catchments. Whether we are able to keep global warming below 1.5°C, most Australians will soon live in flood zones.

This means we must start planning and designing our city to achieve the new normal. For example, we will be accustomed to redesigned parks and gardens that can help us coexist with water.

Change in perspective: rain is a resource, not a waste

Understanding the water cycle is an opportunity to have a positive relationship between plants and people in natural processes. We can learn to think of floods as a regenerative element that improves urban life.

However, urban design has long neglected the opportunities that rainwater provides within urban systems. A conceptual leap is needed to turn the general perception of rain into waste. It can be seen as a non-renewable resource that needs to be protected and reused.

This change has been seen in front-line city experiments. In recent years, cities such as New York, New Orleans and Copenhagen are reorganizing themselves after a catastrophic flood. Here, urban design is revolutionizing the way you use, experience and perceive urban space.

The innovation strategy understands floods as a natural process of work, not resistance. Unstructured, soft and nature-based flood adaptive solutions are replacing centralized and engineered technologies.

These projects actively use climate change to provide a variety of additional benefits. Benefits include recreational spaces, ecological functions, environmental restoration, urban biodiversity and economic regeneration.

Make room for water

The idea of working with water through flood prevention measures based on natural processes has been explored in different ways. These can be grouped into four main strategies.

Sponge space and safety failure: The small and medium green space network absorbs and stores excess water. Almost every urban open space, including the roof, can be part of a decentralized off-grid system.

In Copenhagen, the Climate Resiliency Neighbourhood Program aims to transform at least 20% of public spaces into sponges to reduce flooding in dense urban areas. When needed, a controlled flood of part of the system will avoid problems elsewhere – such as roads. These “safe to fail” spaces can have multiple functions and be used for public entertainment when not flooded.

Variability design: Since the water process is seasonal, the design should reflect variability and periodic flood changes. A more comprehensive understanding of the city’s natural processes is becoming a source of design inspiration, in addition to ecological benefits, it will also generate new spatial expressions.

This is an interesting advancement in urban design, and the ever-changing layout replaces the fixed form. Centralized selection of plant varieties and soil substrates supports spatial variability. A good example is the Billancourt Park in France, where the water defines the ever-changing space of the garden.

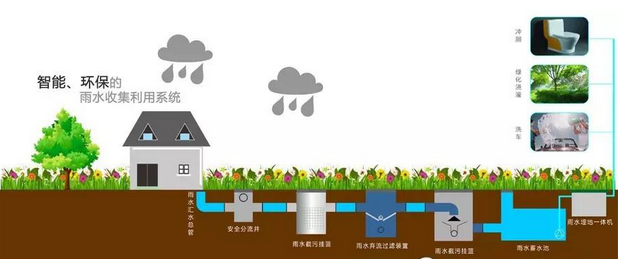

Don’t let it go: Rainwater is a valuable resource that should be retained and used on site. Rainwater should be captured on impervious floors and roof surfaces, rainwater collected and stored for further use, such as irrigation, washing and flushing of the toilet. The process is particularly simple and does not require special techniques, especially for roofing water, which is clean enough to be reused when it is lowered.

Let it infiltrate: paving should allow water to penetrate underground and feed the aquifer. The permeable ground restores the natural water cycle, allowing moisture exchange between the air and the soil. Another benefit is that it cools the city’s space, reduces heat in the summer, and creates a more comfortable habitat.

In order to limit the number of impervious surfaces, roads and parking spaces should be reduced, and asphalt should be replaced by grass or perforated bricks. When paving is required, it should be designed to provide moderate filtration to reduce rainwater impurities.

Need extensive collective effort

The widespread implementation of strategies needed to reduce flooding in the public and private sectors is complex. It requires collective effort.

Studies of urban climate adaptation have shown that flood management planning is usually a top-down process. Post-flood recovery programs rarely have the opportunity for the central government to consider the needs of local communities.

There is a need to make joint decisions on water management to develop resilient communities and help them adapt to a rapidly changing climate. If environmental goals can be combined with sustainability and social equity goals, new challenges can become opportunities.

In addition, the implementation of flood adaptation measures is still too sporadic. It is usually limited to concentrated wetlands in large parks and gardens. Capillary networks are needed to infiltrate dense urban structures with small to medium measures.

However, there is no evidence that the cumulative benefits of these systems will effectively prevent large-scale flooding. Therefore, there is an urgent need to begin systematically testing and monitoring these measures within the city. We need to start asking the question: If every roof has vegetation, if every sidewalk has retention, what if each parking space is a rain garden?

Watching the city’s design and performance in Australia, you can learn a lot from international experience. We have a lot of work to do to adapt this knowledge to the local environment.

We urgently need to apply this knowledge, because if we don’t quickly learn how to use water in cities, then the future water will be more difficult to deal with.

Https://theconversation.com/design-for-flooding-how-cities-can-make-room-for-water-105844