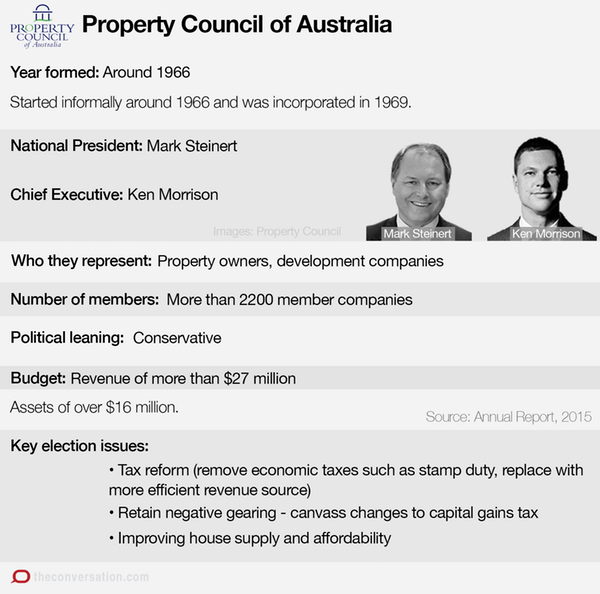

Housing affordability and tax reform have become two decisive issues in this election. The Australian Real Estate Commission – which calls itself “The Voice of Leadership” – helped build the debate on behalf of its 2,200 corporate members.

The committee was originally established in 1969 by the Australian Association of Building Owners and Managers (BOMA) and was renamed the Australian Real Estate Commission in 1996. Its advocacy focus is at the core. The Housing Development Board and the International and Capital Markets Department were established in 2001 and the Retirement Life Committee was established in 2015.

The board of directors is from Australia’s largest residential and commercial developer, while the property committee’s impressive annual income ($27.3 million in 2015) is mainly due to membership fees and services.

Financial risks are high in lobbying for a regulatory environment conducive to real estate development and investment. The property committee’s health budget for advocacy and communication ($6.4 million and $1 million in 2015 alone) generated a large number of reports on taxation and program reforms, advertising campaigns and government opinions. An additional $7.2 million is used for “networking” to ensure that this information is disseminated anywhere.

These huge funds have funded the Council’s high-profile television campaign to maintain negative asset-liability ratios and capital gains tax credits in response to the changes proposed earlier this year. The ad (released on February 22) compares the housing market to a fragile house of cards that is on the verge of collapse, sending out a threatening warning: “Don’t play with the property.”

The government has got the information. Treasury Secretary Scott Morrison served as the National Policy and Research Manager of the Board from 1989 to 1995, and he ruled out changes to the negative gear before the 2016 Budget. Although Malcom Turnbull opposed unfavorable leverage before he became prime minister, he recently changed his stance, refusing to “ruck” changes to existing arrangements, and recommending ambitious buyers. Ask your parents for help.

Although the movement to retain negative debt is most evident by the property committee, behind the scenes, the committee has been busy meeting with the government and writing submissions. In 2015 alone, the New South Wales Department produced 55 submissions and participated in 230 special sessions. Its 2016 electoral handbook presents many “solutions” to “economy through property growth”. Here are some highlights.

Negative gear and CGT

The Board wants to retain a negative asset-liability ratio (which would allow interest rates and other expenses associated with housing investment to be offset by total income) and capital gains tax concessions on investment properties. Despite the large amount of evidence that these bonuses have spurred demand for housing, pushing up prices and making first-time buyers unable to compete. However, by using housing affordability as a manifestation of supply-side pressure rather than demand-side incentives, the Council turned the affordability debate into planning reform.

Housing and planning reform

Current incentives for real estate investment (such as negative debt) do not target new housing supply – only a small portion of investor loans provide funding for new homes. Therefore, the Board believes that the “microeconomic reforms” paid by the Commonwealth to the states should incentivize changes to the planning system to “charge the housing supply pipeline and provide innovative affordable housing solutions.”

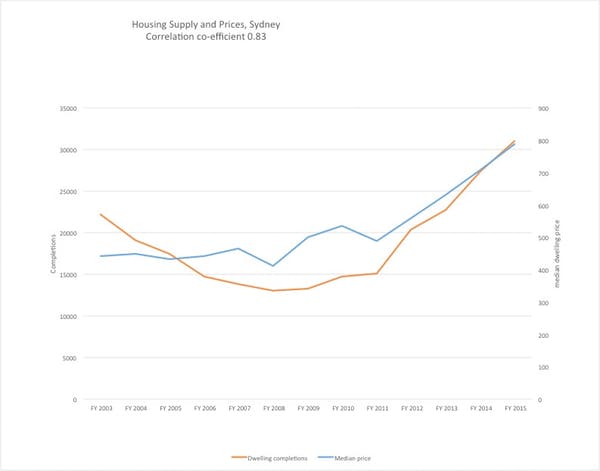

This is a boring argument that ignores the many years of planning reforms that have taken place in states and territories, and the level of new housing production is currently at its highest level in decades. In markets flooded by domestic and foreign investors, this supply can hardly curb price increases.

The property committee is always talking about the bottleneck of housing supply (it thinks it is due to the limitations of the planning system), but this argument ignores an obvious problem, that is, the price is the result of the relationship between supply and demand. The combined effect of negative asset-liability ratios and capital gains tax is to drive demand so strongly during the boom period that prices continue to rise even as supply increases dramatically, especially in today’s low-interest climate.

The table below shows this question about Sydney. It shows that after the economic boom of 1996-2004, when the price tends to be flat, the residential completion rate will slowly decline, but it will rise with the price inflation in mid-2011.

The Council’s electoral platform does require institutional investment in affordable and social housing, which is an idea worth considering.

City and infrastructure

The Property Council supports long-term infrastructure planning and delivery coordinated by the Australian Infrastructure Department. Who is not? But the question is how to allocate costs and benefits. Land value increases due to investments in public infrastructure (eg, new rail lines or roads) are often paid for by landowners and developers.

The Commonwealth and state governments are now discussing value acquisition arrangements that will take advantage of some of these advantages to offset the cost of providing. Instead of this model, the Council recommends the use of tax incremental financing (TIF), which takes advantage of the increase in regional commercial interest rates.

Although popular in certain parts of the United States, it has not proven effective for larger programs. Because our recurring real estate costs are much lower than in the US, it is difficult to implement in Australia.

The Property Council also hopes to return the existing development contributions to existing infrastructure (such as open spaces, local roads and footpaths) and stamp duty on property transactions.

The idea of cancelling stamp duty (at least for domestic buyers) has certain advantages because real estate transaction taxes can hinder liquidity, such as preventing retirees from moving to smaller homes. However, experts believe that stamp duty should be replaced by land tax to encourage more efficient use of land.

This will also provide a mechanism for capturing the value generated by public infrastructure investments. Not surprisingly, the property committee does not think so, but requires a higher GST.

The property committee complained that its members suffered an unfair tax burden, but they seemed content to spend a lot of money on publicity and social activities. Described by economists as “seeking additional spending,” lobbying for a more relaxed regulatory and financial environment is clearly expected to bring high returns to the real estate industry.

But it’s important to remember that despite the sheer size, the Real Estate Commission represents only a portion of the development, construction and real estate industries that do not actually cover many of the smaller suburban developers or home builders. The question is whether the Voice of Leadership will dominate the agenda, or whether people will have a broader view of housing and cities.