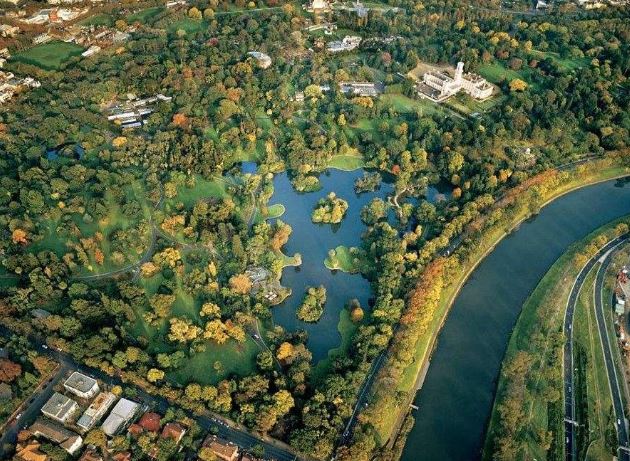

Urban nature plays a vital role in the future livability of cities. An emerging study suggests that bringing nature into our cities can bring a range of truly impressive benefits, from health and well-being to adaptation and mitigation of climate change. In addition to the benefits to people, cities are often hot spots for threatened species and a logical place to make significant investments in conservation. On average, Australia has three times as many endangered species per unit of urban area as it does in rural areas. However, it also means that urbanization remains one of the most destructive processes of biodiversity.

Despite the government’s commitment to greening urban areas, the city’s vegetation coverage continues to decline. A recent report found that local governments in our metropolis are actually going backwards in their greening efforts. Current urban planning approaches often view biodiversity as a constraint — a “problem” that needs to be addressed. At best, biodiversity in urban areas is “offset”, often far from affected sites. This is a poor solution because it does not provide nature where people can benefit most from interacting with it. It has also had questionable ecological results.

Integrate nature into the urban fabric

A new urban design method is needed. This will see biodiversity as an opportunity and a valuable resource to be protected and maximized at all stages of planning and design.

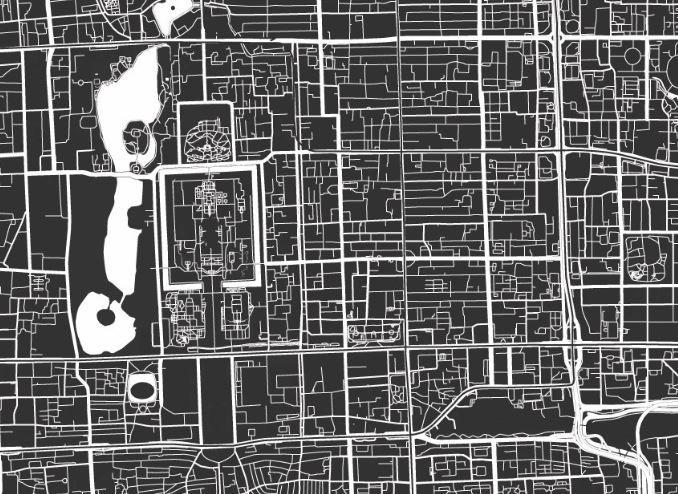

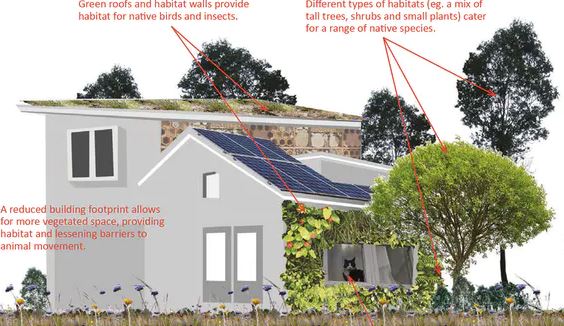

Unlike traditional approaches to protecting urban biodiversity, biodiversity sensitive urban design (BSUD) aims to create urban environments that contribute positively to biodiversity. This includes careful planning and innovative design and architecture. BSUD seeks to integrate nature into the urban fabric by linking urban planning and design to the basic needs and survival of local flora and fauna.

BSUD applies five simple principles to urban design based on ecological theories and understanding:

Protecting and creating habitats

Helps disperse species

Reduce man-made threats

Promoting ecological processes

Encourage positive people to interact with nature.

These principles aim to address the greatest impact of urbanization on biodiversity. They can be used on any scale, from individual houses to region-scale developments. The evolution of BSUD is a series of steps that urban planners and developers can use to achieve the net positive results of any development for biodiversity.

BSUD encourages early development of biodiversity goals, as well as social and economic goals, in the planning process and then the gradual realization of these goals through a transparent process. By articulating biodiversity goals (such as increasing the survival rate of X species) and measuring them (such as sustainability), BSUD enables decision makers to make transparent and scientifically proven decisions about alternative, testable urban designs. For example, in a hypothetical development case in west Melbourne, we were able to demonstrate that anti-cat legislation is irreplaceable when designing an urban environment to ensure the durability of the nation’s threatened legless striped lizards.

What does BSUD city look, feel and sound like?

Biodiversity sensitive urban design represents an entirely different approach to protecting urban biodiversity. This is because it attempts to incorporate biodiversity into building forms, rather than limiting it to fragmented residual habitats. In this way, it can provide the benefits of biodiversity in an environment that has traditionally been considered of no ecological value.

It will also bring significant mutual benefits to the city and its inhabitants. Two-thirds of australians now live in our capital city. BSUD can add value to the range of significant benefits urban greening provides, and help build greener, cleaner, cooler cities that allow residents to live longer, have less stress, and work more efficiently. BSUD promotes human-nature interaction and nature management among urban residents. It achieves this through humanized urban design, such as middle and high-rise buildings, courtyard buildings and broad boulevards. Compared with high-rise apartments or urban sprawl, developments on this scale have proven to offer better livable results, such as active, walkable street views.

What needs to change to achieve this vision?

While the motivation for this approach is compelling, the path to this vision is not always straightforward. Without careful protection of the remaining natural resources, from scattered vegetation to individual trees, urban vegetation is vulnerable to “1,000 felled deaths”. Planning reforms are needed to remove barriers to innovation that offset and enhance biodiversity conservation and enhancement in the field.

Moreover, actual or perceived conflicts between biodiversity and other socio-ecological issues, such as forest fires and safety, must be carefully addressed. Sector-based projects, such as the Green Star system of the Green Building Council of Australia, may be BSUD certified to provide incentives for developers. Importantly, while BSUD has generated a lot of interest, working examples are urgently needed to establish an evidence base for the benefits of this new approach.

Green city agenda

This enthusiasm for “green cities” contrasts sharply with the traditional view that nature is the opposite of culture and therefore has no place in cities. Conventional wisdom holds that the only ecosystems worth preserving are in national parks and wilderness areas outside the city.

We wholeheartedly support the new agenda, but also believe that it is important not to focus solely on instrumental measures such as canopy targets to reduce thermal stress. We should not forget the experience. The risk with instrumental (or, so to speak, exclusive) methods is that they fail to challenge the dividing line between man and nature. This limits people’s access to the places they live and the wider ecological processes that are vital to life.

Isolated instrumental goals also risk portraying urban greening as a “non-political” effort. But we know that’s not the case, and as we’ve seen, green gentrification is on the rise in connection with iconic green projects like the High Line in New York. Affluent suburbs have always had the most green space in the city. It’s one thing to bring nature into the city. Bringing it into our culture and daily life is another matter.