The history of Melbourne’s strategic planning has largely ignored the contributions of Ruth and Maurie Crow. The crow was an early proponent of functional combinations and compact urban development. They did not praise low-density suburban forms, but they also did not promote high-density suburbanization because they must be human in nature.

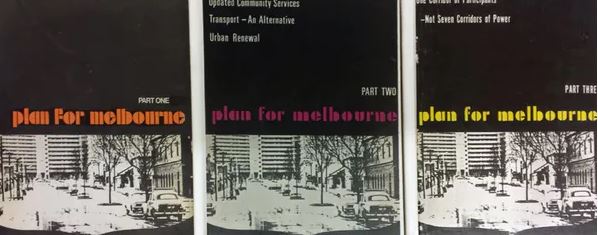

In three Melbourne plans published by Crows in 1969-72, Crows advocated the drive for compact urban development with the ambition of space justice. Re-examining their work provides a balance point in assessing the dynamics of our urban transformation today. Their Melbourne Plan shows a prior understanding of the need to design cities to maximize transportation and interaction:

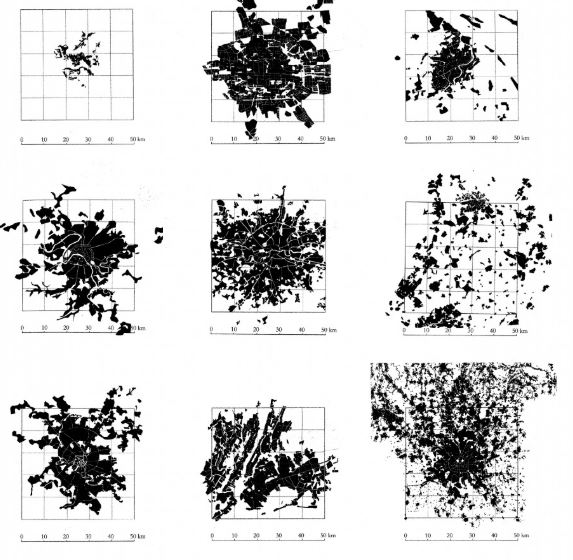

Since the 1980s, this compact city has been a strong representative of Australia’s strategic planning rhetoric. In order to support the growing population in an uncertain social and ecological future, the consolidation of urban areas, the suppression of external growth, and the structure of a multi-core metropolis are considered necessary.

Despite this natural policy ambition, big city planning has achieved what Clive Foster called a “parallel universe phenomenon.” The huge gap between planning intent and urban reality involves justice issues every day, leading to parallel phenomena of justice. Justice ambitions are often attributed to economic rationality-driven urban transformation. For the Raven, the goal of social justice is crucial.

What drives urban transformation?

The history of Melbourne’s strategic planning is marked by the alternating desire for containment and decentralization. Various proposals have surfaced, including “decentralized cities”, “satellite cities”, “growth corridors” and “redirected cities”.

The late 1960s and early 1970s were transitional periods for Melbourne’s development. Urban development has been unrestricted since the 1930s. Now, the growth trajectory of metropolitan areas and central cities has been questioned by the public. The Melbourne Ravens plan was rejected for its seemingly impossible restructuring claim. Instead, in 1971, the Melbourne Metropolitan Council introduced the elusive “growth corridor and green wedge” policy. The fundamental meaning of “clustering”, “squares” and “collectives” proposed by Crow to create an inclusive, convenient, and joyful city has not been considered. The compact urban ideal was not confirmed in official planning until the strategic plan of 1981. Spatial integration then became a de facto policy. The aim is to promote urban population and employment growth, and to make greater use of existing infrastructure and services.

However, market-oriented compaction will result in uneven distribution of social infrastructure, affordable housing, public transportation, and hospitable urban life throughout the city, and inconvenient transportation. The result is a lack of social justice.

Revisiting another city

The Crows is heavily involved in citizen action and is committed to the “Urban Action Movement.” They are amateur planners, heterosexual communists and fanatical community members. They came up with fundamental alternatives to replace what they understood as the injustices of urbanization and capitalism.

They want a city that is more rewarding socially and ecologically. This is their rally cry:

You must plan for the future: a more viable, humane, and ecological future, and then fight for it. Maybe the goal changes as you struggle with it: but without it there is no struggle, only constant class struggle within the system. For the Ravens, urban consolidation has two interrelated goals. The first is to focus social activities, thereby minimizing transport energy. The second is to increase participation.

Cluster, square, collective

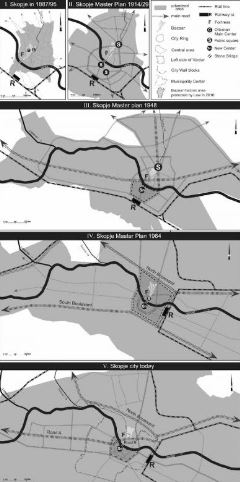

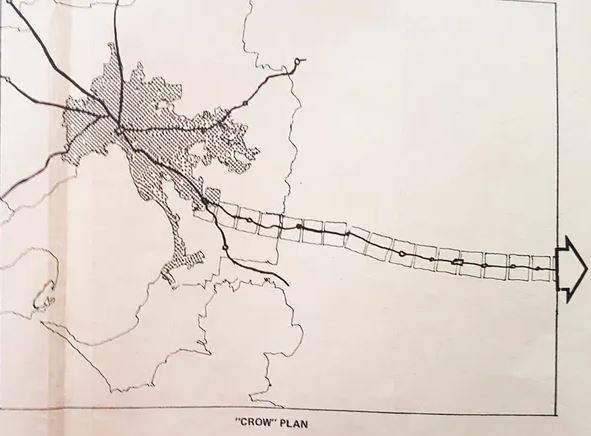

The crow proposes a compact city with well-defined structural elements. In the future of Melbourne, towns will converge southeast along a straight ridgeline. The BRT network will connect a series of “Hearts of Mini Metro” and “Hearts of Urban Metro” to facilitate commuting.

Versatile zoning and high-density cores separate their town from existing suburbs. The Ravens proposed a dedicated first-floor plaza in their Heart of the Metropolis to promote non-commercial contact. These high-density core areas should completely prohibit vehicle traffic to overcome social segregation.

The lobby is designed as a “treatment” to offset the “community distribution trend” of cars. These areas will allow “deliberate voluntary contacts” and encourage interactions beyond the brief and pervasive links of business transactions. The crow’s intention is to provide a space for voluntary collectives to form and develop in order to enhance the “keynote” or “spirit” of the community.

Crow Project

The Crows ’s Plan for Melbourne came up with a radical alternative to what was then proposed by mainstream planners. Their call for compaction comes from the ambition of space justice to minimize alienation, increase access and support the need for social interaction. They proposed the establishment of clusters, squares and collectives to ensure access and inclusion; this was a compression for convenience and not for capital accumulation.

Melbourne has undoubtedly transformed into a vibrant centre since the Raven Melbourne project. Whether it is planned as a fair city is questionable. High density and homelessness are now symbols of the city.

Crows warned 50 years ago that if there was no clear righteous intention to drive the development of the metropolis, we bravely looked back, and it was too late to fight for our citizens to shape cities rather than vested interests.